This is part two of a series on the various Christian doctrines of the afterlife. You can find this in video form (with PowerPoint slides) at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=84HlLjeFKoM&list=PL9Ul79w-MZ05tfZiHYSkW9inwEiwTin_1&index=2

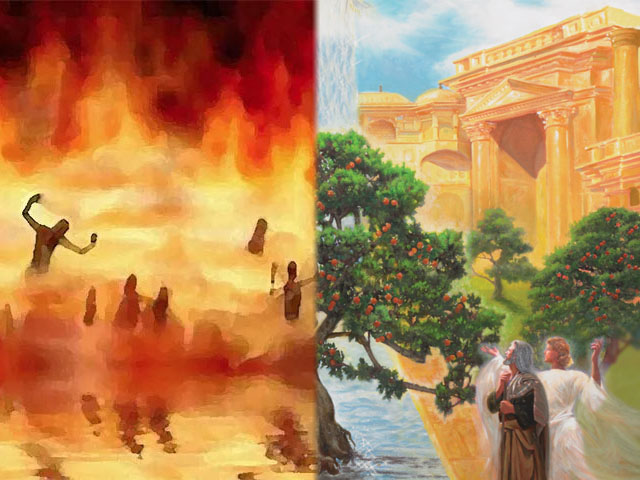

I grew up from about age 5 in an evangelical church environment, and I don’t think it’s possible for any good evangelical to not know all about heaven versus hell, and streets of gold versus fire and brimstone, and to vigorously defend those concepts and then use them to convince people to repent and believe to avoid eternal punishment. But those views are not universal to Christianity, and I just began to realize this in the last couple years. So I’m writing these posts to provide some awareness of the alternatives, and to discuss the doctrinal positions which I believe are probably more correct.

In part one, I discussed the three primary but mutually-exclusive doctrines of the post-death fate of human souls: annihilationism (also called conditional immortality), infernalism (also called eternal conscious torment), and universal reconciliation (also called universal salvation).

In this episode, I’ll continue with considering the topic of whether people can be saved or redeemed after they die, and then the fruits of the various doctrines.

The Question of Post-Death Salvation

A clear challenge leveled against universal reconciliation by ECT apologists is whether someone may die “in sin” and then be saved (such as, entering purgatory and then eventually graduating, so to speak, to heaven).

First, it’s clear that no human will die sinless (except Jesus) (and possibly preborn and infants and children who die before reaching an “age of accountability,” whatever age that may be). The Catholics recognize this, and believe in purgatory as a result (at least, of the elect). Catholics also believe in praying for the dead, understanding that something may change even after death. Many Protestants believe instead that death is a hard and clear dividing line, and that Christ’s sacrifice absolves a believer without the need for post-death purgatory. I find the Catholic position to be dogmatic, not based on specific and clear Bible teaching. I think there is more direct support for redemption by the sacrifice of Jesus – being “covered by the blood,” so that God sees Jesus’ sinlessness instead of our sin. However, a very large fraction of global Christianity believes in the doctrine of purgatory and praying for the dead, and thus I find it compelling that there is a clear allowance for post-death changes in the state of the soul, by both long church teaching and tradition.

On the website of New Apostolic Church Canada has an interesting example of a service for the departed, praying for the salvation of those who died unsaved.

https://www.naccanada.org/IMIS_PROD/NAC/Believe/Service_for_the_Departed/Salvation_after_death.aspx

Some Christians assert that the Catholic view is that only those who have never heard of Jesus can receive salvation post-death. However, I would assert that since the only things we learn about God are from imperfect humans around us, it’s quite arguable that even those who have been told about Jesus have an incorrect or at least very incomplete understanding of Jesus, and as such cannot be held liable for rejecting something false. For example, if someone is abused by a church leader and that informs their understanding of God by example, and they reject “God” as a result, they’re not rejecting the reality of God; they’re rejecting that church leader’s very broken portrayal of God, despite whatever words may be preached each Sunday at that church.

The Bible does describe several cases of post-death conversion. Specifically, John 5:25 discusses the dead hearing the voice of the Son of God, and those who hear will live. Opponents point out that this talks about the succeeding judgement of those who died before Jesus and then come out of the grave, the just to hear and believe and thus live, and the evil to be refuse to hear and thus be condemned. But that’s fine; I believe it’s quite possible to understand the condemnation to be only as long as necessary to purge and purify as discussed above.

That verse in John 5:25 may also be Jesus simply referring to the soon-to-come “harrowing of Hell” as affirmed in the Apostle’s Creed. As such, this is another obvious example of post-death conversion, specifically the idea that Christ preached to the dead and reclaimed those who believed. (The harrowing of Hell is interpreted in many different ways by different denominations and traditions.)

When I read multiple refutations of the idea of salvation after death, they all suffer from the same problems: they start from an assumption that it is impossible (dogma), they also assume that punishment is eternal (more dogma) and therefore interpret all the verses talking about eternal judgment as being permanently triggered at the instant of death (yet more dogma). But this is not clearly stated anywhere in the Bible; every verse that I find used to assert the finality of pre-death choices can readily be interpreted the other way: that the punishment is long (eons) but not eternal, and thus must allow for God’s infinite love and grace and mercy.

The parable of Dives (the “rich man”) and Lazarus is often quoted to oppose post-death conversion, as the gulf between the two men is said by Abraham to be fixed and impassible. However, Jesus often used parables that teach important principles while appearing to violate other Christian ideas, and the point of that parable was not about the eternity of hell. Taking every single portion of every parable as doctrinal is not necessarily wise. For example, it gives Abraham a godlike role in the parable, which is unsupported by the rest of scripture. Or, other parts of the Bible (in keeping with the idea of Sheol’s grey dimness and shades) explicitly describe a forgetfulness of the things of earth once we are dead. Or Ecclesiastes 9:5 says “For the living know that they will die, but the dead know nothing, and they have no more reward, for the memory of them is forgotten.” And Psalm 88:12 talks about “the land of forgetfulness.” Yet in this parable Dives was concerned about his living brothers’ destiny, which violates the idea of forgetfulness in those scriptures. Or as another example, in a different parable Jesus describes a manager praising a steward for shrewdly forgiving the master’s debtors without permission – clearly unethical, yet praised.

Rob Bell wrote an infamous book “Love Wins” in 2011 that enraged many Christians for denying the eternality of hell. It’s not surprising that the outrage comes from evangelical believers, who are deeply vested in the doctrine of hell.

The Fruit of Hell and ECT

Certainly, the majority of evangelical thinkers have settled on the doctrine of hell and eternal conscious torment, but I don’t find the majority position to be compelling simply because it’s a majority position. (Furthermore, it’s not a majority position across all of Christianity.) I find the idea of a deeply-entrenched lie (or more charitably, misunderstanding) that bears much bad fruit to be quite possible. And from my current position, there is much bad fruit in the hell-and-ECT position.

Specifically, in summary, it creates an eschatological instead of missional focus, it teaches that the ends justify the means, it doesn’t actually restrain much human behavior, it divides people from each other and from God, it turns self-sacrifice into a tool for self-promotion, it encourages the use of fear as a tool, and it creates an implicit permission for the use of violence to achieve Christian ends. Let’s look at each of these in more detail:

The entire doctrine of eternal (unchanging and unceasing) reward and punishment creates a focus on the afterlife, not on the present life – focusing only on whatever is necessary in the present life to ensure eternal reward. Jesus was strongly focused on the present life, and “salvation” in his culture referred to the temporal, not eternal. My sense is that a focus on eternal reward has consistently produced far more (not all, but more) human activity that harms people in the present, because it allows all manner of “the ends justify the means” activity.

The threat of eternal punishment for bad temporal activity is insufficient to restrain human behavior even – or especially – by Christians towards the vulnerable; I believe this is because we are naturally wired for the temporal concerns, and any stated concern about the disembodied eternal is more often preempted by our concern about the embodied temporal. In other words, the mental focus on the glorified-body afterlife doesn’t seem to override our necessary focus on our own bodies and pleasures and comforts in the temporal.

It sanctions violence against fellow man, in the name of God’s glory. When one’s doctrine teaches that another human is going to hell anyway, there is little incentive to search deeply for the Imago Dei in that person. Especially when coupled with Calvinism and predestination, ECT allows dehumanization of entire groups of people, reasoning that the chosen believers are better off without the hellbound unbelievers.

It creates an “us/them” dichotomy, rather than a “we” synergy. It violates John 17, where Jesus focused on the oneness of believers, Christ, and God. The Gospel is inherently about man being reconciled to fellow man and to God. ECT inherently creates an adversarial relationship in both cases: it pits God’s glory against man, by making man responsible for shaming God and forcing God to punish man for the sake of God’s glory and reputation; it creates a mindset where the “insiders” (who believe themselves to be heaven-bound) rejoice in their better position than those they perceive as outsiders. ECT and annihilationism and universal reconciliation all address sin in some ways, but ECT is unique in that it creates a structure where God is forced to sequester sinful humans in punishment, explicitly FOR God’s glory. It postulates that seeing people tormented is part of God’s greater glory, by showing the universe the difference between God’s own people, and those who rejected God. This is a lesser glory, by far, than a God capable of winning literally all – every – soul to Himself by patience and love, even if it requires eons upon eons to complete.

It turns groups against other groups. This is nearly identical to the previous “us/them” discussion, but it inherently prevents worldwide peace by forcing ECT thinkers to treat entire people groups as lost, simply because they don’t believe them to know God or be known by God in a way that they can understand. Witness the situation in the Mideast today. Many very vocal Christians would rather that all Palestinians be slaughtered, because they’re Muslims who have (in the Christian perspective) rejected Jesus as Lord. This directly violates the “every tribe, tongue, people group, language” insistence of the Bible. By contrast, most universal reconciliation proponents actively seek worldwide reconciliation, even if they still believe Jesus’ claim as the only way to the Father.

It turns self-sacrifice into a tool for self-promotion. It creates an ethos of “I told them about Jesus so now they’re responsible for their own destiny and I’m no longer responsible for their souls.” What I observe in many Christians today is a sense of washing their hands of the destiny of others, once they feel they’ve done their part to notify them of their eternal destiny choices. It removes incentive to walk together over the long run even if we don’t see a change in their destiny. I firmly believe that this self-interested position has increased the division between perceived insiders and outsiders. If my focus is on my own eternal destiny, then I naturally care more about doing my own part so I “look good” to God, more than about my fellow man’s actual relationship with God, because his relationship is his concern, not really mine. Perhaps this is a broken-human interpretation, but I believe that ECT creates the conditions where this is the default for broken humans. By contrast, for those I know with a universal reconciliation perspective, the focus almost always seems to be on true gospel concerns: loving one another, and loving God, and being patient with someone’s slow (or no) perceived progress. Along with the sense of ultimate security comes a remarkable freedom from insisting (most often in a harmful way) on progress or evidence that the other person meets our own standards.

It creates a permission for violence. If the ultimate judge of our souls will use eternal violence to achieve His ends, there is an implicit permission to use violence to promote the Kingdom. This is clearly antibiblical and directly opposes every teaching of Jesus about the human use of violence.

The threat of hell never will be perceived as loving. It drives a wedge between “the lost” and the God who describes Himself as fundamentally Love. Telling humans that they are sinning will never create motion towards God. On the other hand, a true Gospel of God’s love and infinite desire and patience for relationship with them will always create motion towards God. It’s not our responsibility to convict them of sin; that’s only up to the Holy Spirit, and only the Spirit can see their true hearts and motivations and misconceptions and woundings, and draw them to God.

The threat of hell as an incentive to uncover and repent of sin is an explicit focus on fear, which the Bible repeatedly disavows. The message “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” is infamous for its tone, and unfortunately is held up by many as a gold standard of how to draw people to church. However, it’s not a good model for how to draw people to GOD, instead of church. It explicitly creates a fearful posture before an angry deity, while God repeatedly describes Himself as love, and inappropriately exalts the organization as providing the means for salvation. The more appropriate focus is on love and relationship with God and fellow man. Yes, God is also a just God, but justice does not require fear; the vast majority of references to God’s justice involve a determination to stand up for the oppressed and vulnerable, and bring God’s wrath against those who do not participate in that justice. It’s almost universally a condemnation of God’s own people, not outsiders. Furthermore, God’s wrath is more often presented in the Bible as cleansing and restoring – even the extreme exile to Babylon and the loss of God’s temple was repeatedly portrayed as discipline unto restoration, rather than retribution.

Fruit of Universal Reconciliation

It would not be fair to address the bad fruit of ECT without also considering the fruit of universal reconciliation. Certainly, the proponents of ECT have addressed this as justification for their position. I’ll discuss some counterpoints in more detail in the next part of this series, but some of the arguments include:

- There is no incentive to live for God if God accepts everyone.

- There is no punishment for sin.

- There is no distinction between Christians and other religions.

These suffer from a misunderstanding of the position of most universal reconciliation proponents.

They do not believe there is a lack of punishment; rather, they simply don’t require that punishment to be eternal and thus excessive.

There definitely is a reason to live for God, and avoid what the Bible identifies as sinful. There are two reasons, in fact: one is the multiple promises in the Bible of earthly, temporal salvation for those who live according to God’s Word. The other is avoiding the need to be “refined as if by fire” after the end of our earthly lives.

As to supposedly losing any distinction between religions, the issue is not whether someone believes in Jesus before they die. Instead, universal reconciliation typically asserts that God judges people according to what they do with whatever they’ve been given to understand during their lives (much like Jesus’ parable of the talents). Consider a Muslim who has faithfully followed Allah (the same God of Abraham, by the way; Arabic Christians also refer to the Christian deity as Allah, simply the Arabic word for “God”) but with no awareness of Jesus, or a devout Buddhist who has never read the Bible but seeks human flourishing and selflessness, or even an American who has rejected a false presentation of the Christian gospel by flawed humans who don’t faithfully represent the name or character of God. When such people finally encounter the true and living God in person, it is likely that the Truth (which is far beyond our human comprehension) will be quite familiar and welcome to them, and most universal reconciliation proponents would expect them to be welcomed by God as fully justified.

C.S. Lewis provides a wonderful picture of this in his book “The Last Battle,” when the Jesus-like lion Aslan welcomes into his kingdom as a son the recently-dead Calormene soldier Emeth, who had lived his life for a different god named Tash who opposed Aslan. But Emeth had lived in a way that honored the true god Aslan, who says “I take to me the services which thou hast done to Tash. For I and he are of such different kinds that no service which is vile can be done to me, and none which is not vile can be done to him.”

Yes, Christ said that He was the only way to the Father, but most universal reconciliation believers understand this not to mean that saying the “Sinner’s Prayer” is the only way to heaven, but instead to mean that Jesus’ death and resurrection cleared the way for literally all human souls to be reconciled to the Father, and that we must be careful to not exclude those who encounter and welcome the Truth in deeper ways than we readily see from our limited American evangelical perspective.

Summary of the Bad Fruit Discussion

Certainly, by itself bad fruit is an incomplete metric of the righteousness of a theology or doctrine. A good theology can be corrupted by imperfect humans applying it imperfectly. However, I believe that if good men applying the theology as honestly as possible turns out to produce more bad than good fruit, I have to consider that the theology is in fact deficient.

My Conclusions

I believe part of the fundamental problem with trying to form a coherent doctrine of hell and the eternal destiny of humans is that the Bible simply presents a number of inherently vague and somewhat contradictory concepts. This should not surprise us too much, since

- The Bible was written over more than a thousand years by authors from many different cultural influences, including ancient Hebrew, late Hebrew, Greco-Roman, early Christian, and later Christian (up to 96 years after Jesus).

- Jewish theologians and rabbis are as a rule quite a bit more comfortable with lack of clarity than most modern evangelicals; this flexibility results in confounding diversity within numerous doctrines across the Bible’s pages, and eternal destiny is just one example.

- Due to this diversity, it’s quite possible to take any starting dogmatic view, and find verses to support it, but requiring some gymnastics to handle the verses that oppose it.

We moderns want certainty so that we can be absolutely sure of our rightness of beliefs and thus – particularly in this case – our destiny. But I’ve found myself needing to sit back and admit that this uncertainty obviously does exist, and that only happened once I set aside my dogma and begin to read the text on its own terms, not at my insistence that a certain doctrine is right.

In short, I believe I was changing the Bible’s meaning based on my dogma and doctrine, instead of letting the Bible change my doctrine and dogma.

I believe that my former insistence on certainty showed a lack of faith in God’s inherent goodness, love, and mercy. We humans, especially modern humans influenced by the Enlightenment and the Age of Reason have a need to “get it right,” so we end up with thousands of divergent denominations with differing doctrinal positions, each vigorously and passionately defended by its members as the only faithful and orthodox Christian answer, even though they are often incompatible with each other.

I think the far harder, yet far more honest and wise approach, is to simply admit we don’t know the answers. For that reason, I feel significant liberty to not be bothered by the uncertainty, and to select what most closely comports with my overall sense of God’s revealed character and the overall balance of all the references to eternal destinies.

Thus, I would call myself a hopeful universalist. I fully recognize the presence of annihilationist passages, despite the clear presence of universalist passages. In considering the overall thrust of Scripture, I find universal reconciliation to be more in line with my understanding of the nature of God and God’s relationship with man. But I cannot perfectly prove universal reconciliation – nor can I perfectly disprove annihilationism – from scripture.

However, I do utterly reject the assertion that the doctrines of hell and ECT are entirely right and correct and “biblical,” because when I read the Bible without the ECT filter with which I grew up, I see too many clear things that refute those positions, even in the very verses ECT believers use to justify their doctrine.

For these reasons, I’ve chosen – and I readily admit it is a choice – to reject the traditional evangelical doctrine of eternal conscious torment and the corresponding doctrine of an eternal hell managed by God and the righteous angels, that exists for the purpose of retribution against nonbelieving humans and rebellious angels, with no chance of future repentance.

Instead, I chose to embrace the doctrine of an infinitely loving God whose son Jesus already fully redeemed every human, and will be infinitely patient in bringing every single one of them to restoration and reconciliation with God and fellow humans.

Next time we’ll talk about some specific verses that are used to develop the doctrine of eternal conscious torment, talking about long-lasting punishment and topics like fire and brimstone, and why I don’t find them to be persuasive towards the ECT doctrine.

I hope this has been helpful to you. I’d love to hear your thoughts about this, and I’ll entertain any polite and honest discussion on the matter.