This is part three of a series on the various Christian doctrines of the afterlife. You can find this in video form (with PowerPoint slides) at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pmpdSkc6Bww&list=PL9Ul79w-MZ05tfZiHYSkW9inwEiwTin_1&index=3&pp=gAQBiAQB

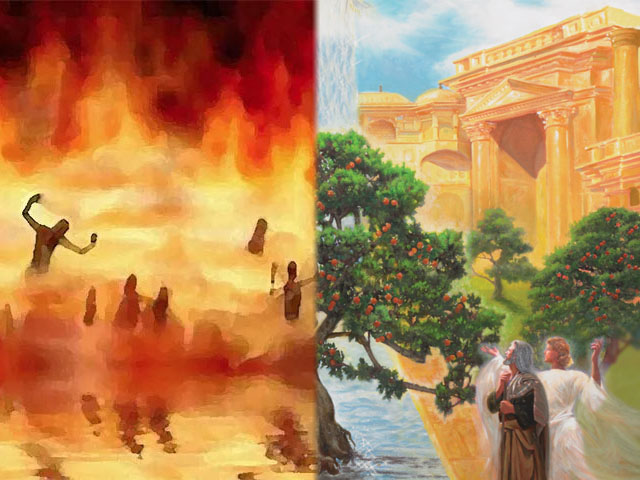

I grew up from about age 5 in an evangelical church environment, and I don’t think it’s possible for any good evangelical to not know all about heaven versus hell, and streets of gold versus fire and brimstone, and to vigorously defend those concepts and then use them to convince people to repent and believe to avoid eternal punishment. But those views are not universal to Christianity, and I just began to realize this in the last couple years. So I’m writing these posts to provide some awareness of the alternatives, and to discuss the doctrinal positions which I believe are probably more correct.

In the first part, I discussed the three mutually exclusive doctrines of annihilationism, infernalism, and universal reconciliation. In the second part, I discussed the fruit of the various doctrines, and the question of post-death salvation. This time, I’ll be discussing several categories of afterlife information found in the Bible.

To very briefly recap part 1, the Bible contains four dramatically different Greek and Hebrew concepts of the afterlife, Tartarus, Sheol, Hades, and Gehenna. Taken together and assumed by many Christians to refer to the same thing, together with a misreading of the Greek word “aionion” as “forever and ever and eternally without end,” the doctrine of hell tries to fuse them into a single concept of a place of eternal punishment. There are three main doctrines about what happens when we die: Eternal conscious torment, annihilationism, and universal reconciliation.

To briefly recap part 2, the Bible is often interpreted by evangelicals to mean that once we die, any chance of redemption disappears, but there are plenty of places in the Bible that this topic is challenged. Also, I concluded that Eternal Conscious Torment has a lot of bad fruit, and Universal Reconciliation has a lot of good fruit; most of the objections to Universal Reconciliation by evangelicals are founded on misinformation and mistaken beliefs.

With that general background, I have concluded that universal reconciliation is the most trustworthy interpretation of the Bible’s various references to the afterlife (as discussed in the first two episodes). But they were fairly tightly focused on those three divergent doctrines as expressed by those four terms for the afterlife. I didn’t get deeply into other references to the afterlife in the Bible, and I don’t think it’s fair to settle on the doctrine of “universal reconciliation” without also diligently addressing objections to the idea. The best debates consider all sides of the issue, without shirking any troubling opposition. Otherwise, one may rightly claim that the arguments were simply cherry-picked to only address the easy issues. Such a debate would be deceptive rather than convincing. I’d much rather you had the entire matter to consider, rather than being persuaded by an argument that omits any controversy.

In light of my determination to diligently consider all sides of this matter, I recognize that the Bible doesn’t just address “hell” only in its various words of Gehenna, Hades, Sheol, and Tartarus. It also clearly discusses painful afterlife punishments in other words and concepts that can strengthen or weaken various views of afterlife punishment. For a full understanding, these verses also need to be carefully considered.

So I’d like to discuss several categories of afterlife information found in the Bible:

- the severity of punishment of sin (such as “fire and brimstone”)

- the finality of punishment (whether sinners are annihilated, or tormented endlessly, or redeemed)

- the duration of punishment (is it truly eternal, without end)

- the permanence of the afterlife (whether death is also eternal if life can be eternal)

- who is the target of judgement by fire (was “hell” designed for torturing humans)

- is God vengeful (does God inflict pain for pain’s sake, or to redeem and restore)

Fire and Brimstone

Some people arguing against the evangelical concept of hell say that brimstone (theiou in Greek, or gophrith in Hebrew, known today as the element sulfur) was used for healing. Sulfur can in fact be used to treat skin conditions, and smoke from burning sulfur was in fact used for fumigation. Some people therefore argue that “fire and brimstone” referred to a healing fire, not vengeance and judgement. But references to brimstone are actually never used that way in the Bible. Every single reference to brimstone – all 14 of them – was to its destructive or hot-burning properties. Sulfur was widely known to be inflammable and so it is used to emphasize and strengthen the idea of hot, unquenchable fire – in contrast to a warming or comforting or cooking fire. Furthermore, the disgusting smell of the toxic smoke from burning sulfur makes such a fire all that more unpleasant and dangerous to be around (or, obviously, to be trapped in).

However, to a listener in antiquity, the connection of brimstone to fire would also convey the idea that such a fire was in some sense a cleansing or purifying agent. Fire is very often portrayed in the Scriptures in relation to refining, such as in Rev 3:18, which says “I counsel you to buy from me gold refined in the fire.” In refining, fire is used to either burn out impurities like carbon, or to separate lower-quality metals from the desired precious metal. Sulfur adds to this idea in specific ways. First, sulfur was used in the refining of gold in antiquity. It was used in the extraction of mercury from cinnabar ore, and the mercury was then used to purify the gold.

https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=73830

Also, sulfur can help to directly extract precious metals from alloys and ores; it binds to the base metals to form sulphides, while the precious and heavy metallic gold does not as readily react with the sulfur and sinks to the bottom of the smelting pot to be removed at relatively high purity.

https://www.911metallurgist.com/blog/sulphur-refining-gold

Finally, “gold parting,” the separation of gold from silver, was also practiced in antiquity using sulfates, as far back as the fourth millennium BCE, but in significant practice by the first millennium BCE.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gold_parting

With all this in mind, I think it’s safe to say that while references to brimstone were NOT used in the Bible to indicate any kind of healing or medicinal purpose, brimstone was nonetheless widely understood as an agent of purification by fire, instead of merely destruction. I suppose this added some complexity to the simple idea of fire. It also probably offered a useful cultural reference to Sodom and Gomorrah, in that those cities were in an area with large sulfur deposits, and thus referring to “fire and brimstone” would have brought to mind the legendary fate of those cities.

While we are on the topic of fire, perhaps we should also wrestle with 2 Peter 3:7, which says “by His word the present heavens and earth are being reserved for fire, being kept for the day of judgment and destruction of ungodly men.” This would be in line with annihilationism. However, consider the immediately preceding verse in 2 Peter 3:6, which referring to the Great Flood, says “through which the world at that time was destroyed, being deluged with water.” The concept of destruction presented here, in parallel verses, is clearly not utter destruction to the point of nonexistence. The world was purified by the Great Flood – God specifically said that was the purpose of the flood – so that it could be repopulated with righteousness. And just a couple verses later, in 2 Peter 3:9, it says “the Lord is not slow about His promise, as some consider slowness, but is patient toward you, not willing for any to perish but for all to come to repentance.” So in chapter 3 it seems that the writer is interested in portraying a God who will patiently, eventually, and utterly cleanse and purify and restore everyone.

Finality

What about the finality of afterlife judgement? Those who prefer the doctrine of annihilationism insist that the judgement leads (either immediately, or after some pain) to complete nonexistence of the human soul.

Jesus often refers to the punishment for wrongdoing in terms of casting evildoers or evil deeds into fire. For example, in Matt 3:10 and Matt 7:19 and Luke 3:9 and others, Jesus says that every tree that does not bear good fruit is cut down and cast into the fire. In Matt 3:12 He says that the chaff will be cast into unquenchable fire. In Matt 13:40 He refers to tares or weeds being burned up with fire. These and many similar examples are used by those who believe in annihilationism – the doctrine that God will simply destroy the souls of sinners, rather than eternally torment them or universally save them, just as fire rapidly and permanently consumes pruned branches.

However, Jesus also often said that those God loves, God prunes. The undesirable parts that are being removed are burned up, yes, but the goal is the pruning and perfecting of the one that is pruned, not their destruction. It’s not about the branches, it’s about the remaining fruit-bearing plant.

Even if we insist that “every unfruitful tree” refers to “every unfruitful human,” the metaphor of a tree being cut down and cast into fire is still open to this redemptive interpretation: cutting down a tree leaves its root and stump in the ground. As anyone familiar with gardening and forestry knows, the result of this is usually that the tree (or many other plants, including frustratingly resilient weeds) will simply regrow in the next season, if not sooner. There is still life in the stump, and some trees and plants are actually quite hard to kill by merely cutting them down. You’ll know what I mean if you’ve ever tried to permanently get rid of an unwanted holly tree. Dozens of fresh shoots pop before long from even small roots that are missed.

What is destroyed, at any rate, is the unfruitful portion. Yes, that cutting would be quite disruptive and force the plant or tree to start from scratch, trying to build something fruitful – but it’s not inherently deadly to the plant. Now, just as the Bible uses parables and metaphor, this is also just a metaphor. But I think it makes the point that pruning – even to the most extreme form of cutting down to a mere stump – is not destruction of the entire plant. (For example, a grapevine can be cut all the way down to the root, and it will completely regrow the next year. In blueberry husbandry, that is actually a preferred way to prune every year: simply mow the field down to the ground every winter. The plants actually grow back healthier and more fruitful the next season.) When we couple this pruning imagery with other Biblical statements of God’s determination to save and redeem all, it’s hard to accept annihilation as God’s best intent.

Also, the idea of destruction is hardly insistent upon annihilation. Many things are functionally destroyed without being annihilated. For example, in Matt 9:17, Jesus says “nor do people put new wine into old wineskins; otherwise the wineskins burst, and the wine pours out and the wineskins are ruined.” Yes, the wineskins are functionally destroyed – but not annihilated. Yes, the wine is ruined, but it still exists, only mingled with dirt on the ground.

Regarding the Great Flood, note that the “destruction” of the earth by the flood was not destruction unto nothingness, but a return to primordial lack of order, ready for rebuilding and repopulating into righteousness.

Similarly, destroying the body does not automatically destroy the soul. In fact, perhaps we could say that instead it prepares the soul to be reborn and restored.

A verse often proposed as a potent argument for annihilationist theology is Matthew 10:28, which says “And do not fear those who kill the body but are unable to kill the soul; but rather fear Him who is able to destroy both soul and body in Gehenna.” This certainly seems quite final: not only the body, but also the soul. I think most Christians, even those who believe in eternal undying hell, would assert that God is well able to take such a final action, but I also don’t think this verse states any intent on God’s part to do so, especially when contrasted against other very forceful statements of God’s intent to redeem everything God has created. The ability and the intent are quite different. So I believe this verse to be a statement about God’s power, not about God’s desire or plans for handling sinners.

One other thing is worth noting. Jesus frequently referenced Gehenna, a very real place to Himself and His audience, with discussions of its “unquenchable” fire, including the use of the word aionion. But one only needs to visit Jerusalem today to discover a pleasant if somewhat unpopulated valley south of the ancient city center. Perhaps the lack of housing or businesses there are due to some Jewish superstition that still lingers about its unclean past, but today there are certainly no eternal fires burning there. If we want to take Jesus’ words very seriously, such as Matt 18:8-9, then the fact that the “unquenchable” “eternal” fire of Gehenna has long been extinguished should challenge our understanding of aionion as meaning “without end,” which might require us to rethink our dogma about the “eternal” fire of hell.

One other brief note here: when in Matt 18:9 and Matt 5:22 when Jesus refers to “the fires of hell” as it is usually translated, it’s worth looking a little closer. The original Greek says it this way: “ten geennan tou pyros,” or literally, “into the Gehenna of the fire.” Do you see how that got flipped around in most modern Bibles? All the literal translations, and many older non-literal translations (English Standard Version, Berean Literal Bible, American Standard Version, Lamsa Bible Aramaic translation, Aramaic Bible in Plain English, English Revised Version, Literal Standard Version, New Revised Standard Version, Weymouth New Testament, World English Bible, Darby Bible Translation, and the Young’s Literal Translation) use this older ordering where the Gehenna is a property of the fire. But the newer translations, based on the doctrine of hellfire, flipped that around to the fire being a property of a place called hell. This should make us pause and carefully consider whether our doctrine drives our reading. Instead, our reading should affect and shape our doctrine.

Duration

How long does the punishment last?

Daniel 12:2 says “And many of those who sleep in the dust of the ground will awake, these to everlasting life, but the others to reproach and everlasting contempt.” The Hebrew word translated here as “everlasting” is olam, which much like the Greek word aionion is better understood as “for a long time,” not “eternal.” For example, in Jonah 2:6, Jonah says that he was in the great deep for “olam,” which was actually for three days, not literally forever. I’m sure it would have felt eternal in the middle of it, but it was for a specific time, consistent with most other uses of olam. (Also notice here that this verse would tend to discount annihilationism, if the ones needing punishment awaken to age-long contempt.)

Plenty of New Testament verses use aion or aionion for things that are clearly non-eternal. As a good example, in Matt 24:3, the disciples ask Jesus “what will be the sign of Your coming and of the end of the aion?” Or 1 Cor 10:11, where it says “these things happened to them as an example, and they were written for our instruction, upon whom the ends of the aion have arrived.” Clearly the word aion or aionion can be used for definitively limited durations. The simplest translation of aion is “age” and of aionion is “age-long.”

Other similar examples are discussed here: https://www.hopebeyondhell.net/articles/further-study/eternity/

One excellent quote from that article in Hope Beyond Hell says this:

“Augustine raised the argument that since aionios in Mt. 25:46 referred to both life and punishment, it had to carry the same duration in both cases. However, he failed to consider that the duration of aionios is determined by the subject to which it refers. For example, when aionios referred to the duration of Jonah’s entrapment in the fish, it was limited to three days. To a slave, aionios referred to his life span. To the Aaronic priesthood, it referred to the generation preceding the Melchizedek priesthood. To Solomon’s temple, it referred to 400 years. To God it encompasses and transcends time altogether.”

There are plenty of references to aionion fire and torment that must be addressed. For example, in Matt 3:12 Jesus says that the chaff will be cast into unquenchable fire, and in Mark 9:48 He says “where their worm does not die, and the fire is not quenched.“

I would note that discussions of pain and punishment are always far more likely to be overstated than understated. One does not understate in order to persuade. And Jesus most often spoke in parables and metaphors, not literalisms.

At any rate, we have some challenging verses in Revelation to consider.

Rev 14:9-11 says “If anyone worships the beast and his image, and receives a mark on his forehead or on his hand, and he also will drink of the wine of the wrath of God, which is mixed in full strength in the cup of His rage, and he will be tormented with fire and brimstone in the presence of the holy angels and in the presence of the Lamb. And the smoke of their torment goes up forever and ever; they have no rest day and night, those who worship the beast and his image, and whoever receives the mark of his name.“

Rev 20:10 says “And the devil who deceived them was thrown into the lake of fire and brimstone, where the beast and the false prophet are also, and they will be tormented day and night forever and ever.“

“Forever and ever” certainly sounds like eternity. But again, this is a feature of the translation which is biased towards the evangelical sense of “without end.” It’s actually the same root word aionion, just doubled up here for emphasis. The literal reading is “And the smoke of their torment goes up to aionias aionion” – it goes up “ages of ages.” Yes, it’s a very long time, but this hardly conveys the modern sense of “forever” or “eternal” or “without any end.”

Regardless of that mistranslation, my sense is this: it’s the fire of purification that is unending, not our presence in that purifying fire. Any person will only be there as long as necessary for the required purification. Anything more is fundamentally unjust. And I do not accept the argument that any sin against a perfectly and infinitely pure and holy and just God is therefore worthy of infinite punishment. That defies logic, and it’s exactly the kind of statement that would be made by someone who was trying to find an apologetic for infinite punishment by a loving God. Instead, as Hebrews 12:29 says, “our God is a consuming fire” – God (who is eternal) is identified AS fire, an aspect of God’s nature. Thus that fire certainly is eternal, consuming anything not godly, and so to be in God’s presence is eternally purifying – but for those submitted fully to God’s Lordship, it will not be eternally painful, but instead, once the purifying has been accomplished, will be eternally warming and comforting.

We also need to consider Isaiah 66, which concludes with these words: “All mankind will come to worship before Me. Then they will go forth and look on the corpses of the men who have transgressed against Me. For their worm will not die and their fire will not be quenched; and they will be an object of contempt to all mankind.“

Most people who believe in eternal hell believe this to mean essentially that all the righteous will look with contempt upon all the unrighteous suffering in an unending hell.

But that reading is inherently contradictory, since “all mankind” (which if we understand “all” in its plainest meaning includes both righteous and unrighteous) will look on the corpses of those unrighteous who didn’t worship God. And all mankind will be looking on their corpses, not on their souls. Instead, we can make a subtle shift in understanding, which I think is perfectly in line with the words in Isaiah 66: the worm and fire OF THE CORPSES will never die. But all human souls will be raised into new incorruptible bodies on the last day, to judgement or reward. So it seems to me that the simplest understanding here is that there will be a bodily judgement at play, as discussed in Revelation in the final battle, and those corpses will later be looked upon in contempt, as evidence of God’s overwhelming power to win the final battle. But the eternally-living souls (regardless of the state of their dead bodies) do not need to be eternally condemned for this to be possible. And I find it’s a stronger statement of God’s ultimate power and love, to conclude that someday every soul will worship freely, and look with appropriate but repentant contempt on their own former corpses which opposed God during their lives.

Eternal death versus eternal life

Much has been made, in debates about the afterlife, of the concept of eternal life mandating that punishment after death must also be equally eternal.

It might be best to start with the cornerstone verse used by evangelical theologians to express the essence of the Gospel, John 3:16, which says “For God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son, that whosoever believes in Him shall not perish, but have eternal life.” Ironically, while this verse is heavily used by people who believe in eternal undying hell, this verse is perhaps the best statement of annihilationism – that Jesus saves us from perishing. But if we review the Gospels, we find that Jesus nearly always used the word “saved” or “salvation” in a very temporal sense – to refer to restoring or reclaiming life and health and well-being on earth, not in an eternal or afterlife sense. Our modern Christian sensibilities have transformed that word to refer to the afterlife, so we read it with the eternal meaning in mind, but Jesus usually appears to have meant otherwise in His teachings. Also, note that the word “eternal” is, once again, aionios. Perhaps a more accurate translation would be “whosoever believes in Him shall not perish but have full life in this age.” So as strange or offensive as this concept may be to an evangelical, it seems that John 3:16 actually doesn’t have that much to say about eternal – unending, infinite, forever – life or death. So in that sense, His statement in John 3:16 has a different flavor.

Note that in the very next verse, John 3:17, Jesus goes on to say “for God did not send the Son into the world to judge the world, but that the world might be saved through Him.” If anything, this has a very universal-reconciliation flavor to it – that the world (not limited to those who believe) might be saved. Evangelicals usually tie the “believed in Him” to “saved,” but Jesus, for some reason, didn’t say “whosoever believes in Him will be saved.” Those two concepts appear to be somewhat decoupled here: whoever believes in Him will have eternal life; God sent Him to save the world.

This is a bit off-topic for the eternal life versus eternal death topic, but it seemed best to address it here as a bit of a sidebar. So back on topic…

Perhaps the hardest thing for me to explain from a universal reconciliation standpoint is Jesus’ discussion of the sheep and the goats in Matt 25:31-46, even though that verse is deeply important to my current understanding of the requirements the Bible places on the people of God. The last verse of this passage, Matt 25:46, says “And these will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life.” The same word, aionion, is used in both instances. If we believe in eternal life as a reward, then this verse would logically imply that the punishment is also similarly eternal (in our modern sense). However, this mirrors the duality in Romans 5:18-21, which says “So then as through one transgression there resulted condemnation to all men, even so through one act of righteousness there resulted justification of life to all men. For as through the one man’s disobedience the many were appointed sinners, even so through the obedience of the One the many will be appointed righteous. Now the Law came in so that the transgression would increase, but where sin increased, grace abounded all the more, so that, as sin reigned in death, even so grace would reign through righteousness to eternal life through Jesus Christ our Lord.” Clearly “eternal life” and “eternal punishment” in Matt 25 ought to have the same meaning of “eternal” – but so should the meaning in Romans 5 of “all” be the same for both those who were affected by Adam’s sin and those who are saved by Christ’s obedience.

How do we handle this disconnect?

What tips the scales for me is Romans 5 saying “grace abounded all the more,” which clearly indicates that God’s grace for literally all overcomes the sin of all. What do we do then with the “eternal” punishment? Once again, consider that aionion means “age-long.” Those who turn to Christ eat regularly of the tree of life, and their life will be sustained as long as they do so – and I cannot imagine that anyone who has tasted the goodness of God will every choose to stop eating of the tree of life. Those who reject Christ will suffer age-long punishment – but grace abounds, and the moment that they repent and turn to Christ, I believe that the aion of punishment will end for them, and the new aion of their resurrected life will begin.

We also have to consider Rev 20:14-15, which says “Then death and Hades were thrown into the lake of fire. This is the second death, the lake of fire. And if anyone’s name was not found written in the book of life, he was thrown into the lake of fire.” The “second death” sounds quite permanent. But consider that the first death is not permanent: God will raise every man to judgement. I therefore don’t see any reason to believe that the second death is permanent. Notice that aparabaton, the word translated “permanent” or “unchanging,” appears only once in the New Testament in Hebrews 7:24, referring to Jesus’ unchanging or permanent priesthood. If the New Testament’s authors had wanted to refer to punishment as permanent or unchanging, one might reasonably expect them to use this word instead of aionion.

Who is the target of judgement by fire

I think it’s also worth investigating who God intends to judge by fire. Some of the relevant verses are:

- Matt 25:41, where Jesus says “into the eternal fire which has been prepared for the devil and his angels.” This indicates that the “eternal” fire was not prepared for man, even if it is temporarily used to purify the souls of unrighteous humans.

- Mark 9:49, where Jesus says “for everyone will be salted with fire.” This makes no distinction between righteous and unrighteous men. It’s quite simply “everyone.” The Greek word for “all,” “pas,” is very simple: all, the whole, every kind. This is actually in line with Catholic thinking, which understands that even the righteous will need final purification after death before being able to enter the perfect holy presence of God.

- Luke 3:16-17 where John the Baptist says “He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire” and “He will burn up the chaff with unquenchable fire.” In a pair of back-to-back verses, John indicates that even those who will be baptized in the Holy Spirit will also be baptized in the fire that burns up the chaff. As above, this indicates to me that the fire’s purpose is purification, not destruction, and it applies to both good and evil humans.

- 1 Cor 3:13-15 which says that “each man’s work will become evident, for the day will indicate it because it is revealed with fire, and the fire itself will test the quality of each man’s work.” … “If any man’s work is burned up, he himself will be saved, yet so as through fire.” Again, the fire is not just for the unrighteous, but also to purify every man and their works.

Two verses in Revelation address the lake of fire: Rev 20:14-15 says “Then death and Hades were thrown into the lake of fire. This is the second death, the lake of fire. And if anyone’s name was not found written in the book of life, he was thrown into the lake of fire.” And Rev 21:8 says “But for the cowardly and unbelieving and abominable and murderers and sexually immoral persons and sorcerers and idolaters and all liars, their part will be in the lake that burns with fire and brimstone, which is the second death.” Nothing in these verses indicates the permanence of presence in the lake of fire. Depending on one’s existing dogma, one can read temporal purification into this, just as readily as reading eternal torment into it. Also, we cannot forget that even justified people can be guilty of these sins – Paul called himself the worst of all sinners, certainly a murderer and unbelieving before his conversion.

The usual response of those who insist on eternal conscious torment is that these verses in Revelation only refer to those who die as unrepentant sinners. But there are two problems with such logic: For one, that would apply to any sins, not just this short list, and I doubt that any human is completely repentant of every single kind of habitual sin. For another thing, it’s reading something into the text that isn’t there (eisegesis). It’s insisting on a certain reading based on a dogma, rather than letting the verse simply speak for itself. As with many of the other verses noted above, when we approach them with a certain end goal, we’ll find what we want.

One other note about post-death judgement: the Catholic assertion about purgatory, to me, seems to miss a critical point about the Gospel. We believe that in some mystical sense Jesus lives in the heart of all who believe in Him, and who live their lives according to His teachings. We regularly use the phrase “God with us, God in us.” If we insist that humans must be purged of their unrighteousness (the root of the word “purgatory”) before entering God’s presence, how can that be if God already lives in us? We are already in God’s presence on a very deeply intimate level before we even die. Our bodies are certainly corrupted, and this idea was deeply rooted in the Old Testament teaching that “no man may see God and live” (Exodus 33:20). But if our souls are made so acceptable to God by the work of Jesus on the cross that God’s own self comes and lives in our very hearts while we are still alive, then what possible fear do we have of entering God’s holy presence after death? Certainly there will still be unholy aspects of our character that need refining and purification, even for the most righteous human, but it doesn’t seem like God has a problem with being intimately in our presence as we are right now, and our sins are already “covered by the blood” as we like to say.

So in that sense, every one of us is subject to purification by fire – by the refining purifying presence of God’s holiness – not just those who are unrighteous while on this earth.

Many people supporting eternal conscious torment address the justice and righteousness of God, which cannot tolerate sin and must punish it to balance the scales. And there is certainly much evidence in the Bible of God exacting vengeance on humans, both individuals and entire nations. And it’s not just the Old Testament, even though some Christians insist that the God of the Old Testament is portrayed rather differently than the God of the New Testament. This was the origin of one of the early significant heresies, known as Marcionism; Marcion preached that the Old Testament and the New Testament deities were not in fact the same god. No, God’s vengeance even appears in the New Testament – actually quite a bit in Revelation.

Is God Vengeful?

So if we want to believe in universal salvation or universal reconciliation, what do we do with verses like 2 Thess 1:7-9, which talks about the vengeance of God? It says “to give rest to you who are afflicted and to us as well at the revelation of the Lord Jesus from heaven with His mighty angels in flaming fire, executing vengeance on those who do not know God and to those who do not obey the gospel of our Lord Jesus. These will pay the penalty of eternal (aionion) destruction, away from the presence of the Lord and from the glory of His might.” Or consider Romans 12:19 which repeats an Old Testament verse saying “vengeance is mine; I will repay, says the Lord.” There are plenty such verses, 57 in total, and there are plenty of similar words and phrases discussing God’s punishment inflicted on unbelievers and sinners and evildoers. For this discussion I will limit my comments to vengeance.

For one thing, the word translated vengeance (ekdikesis) has other meanings, including “full or complete punishment.” The word study in Strong’s for ekdikesis says this: “a feminine noun derived from 1537 /ek, “out from and to” and 1349 /díkē, “justice, judge”) – properly, judgment which fully executes the core-values (standards) of the particular judge, i.e. extending from the inner-person of the judge to its out-come (outcome).“

This suddenly sounds a lot less like “vengeance” in the modern concept, which has a connotation of being damaging and harmful. Instead, as “judgement which fully executes the core values of God the righteous judge,” it sounds a lot like perfect justice, where exactly and only enough judgement is properly administered.

As another example of vengeful language, Rev 14:10 says that whoever worships the beast “will drink of the wine of the wrath of God, which is mixed in full strength in the cup of His anger; and he will be tormented with fire and brimstone in the presence of the holy angels and in the presence of the Lamb.” What does that word “tormented” mean? The Greek word basanizo shows up twelve times in the New Testament, and often (but not always) does have a sense of the ruthless infliction of pain or torture. That doesn’t seem to line up with a God of justice or love. But that word also has another rare but real meaning in Greek: to carefully examine something, to probe at it until its essence is fully understood and exposed. We’ve already considered that “fire and brimstone” were often considered as purifying agents, not only as destructive. While the weight of the usage of basanizo in the Bible leads to a harsher understanding, I think there’s room here to see it quite a bit differently. Furthermore, even if one insists on a torture meaning of that word, please note again the lack of a specified duration here: there is plenty of allowance in this verse for a temporal and just punishment, not a vengeful unending torture.

Finally, it’s worth noting that the majority of the instances of vengeance, ekdikesis or the Hebrew equivalent naqam, have a sense of temporal application. In fact, in several instances in the Hebrew Bible, such as Proverbs 6:34, it shows up as “the day (yom) of vengeance,” implying a specific period, not an eternity. Vengeance carries with it a strong sense of justice, which in Biblical terms was very measured and “an eye for an eye.” This would clash with any understanding of eternal, unending torment.

That’s all we have time for in this episode. Next time we’ll talk about scripture and confirmation bias, and consider some of the misunderstandings of universal reconciliation. I hope this has been helpful to you. I’d love to hear your thoughts about this, and I’ll entertain any polite and honest discussion on the matter.