In the last few years, quite a few followers of Jesus in America have been feeling as if they no longer recognize their once-familiar surroundings. Even as institutional Christianity has watched its attendance fall steadily, to the tune of well over twenty million attendees disappearing since 2000, it has doubled down and insists that culture is attacking the church, that the decline is symptomatic of demonic attacks, and that Christians must stand up and defend traditional church culture and morality. But those who are walking away from the church increasingly recognize that something is deeply wrong with the Christian culture in America. They recognize that the decline may be far more self-inflicted than externally-driven. But as they walk out of the familiar church doors, there is a true sense of being shut out, exiled, within their own land. Something is clearly deeply wrong within the church, and they are no longer welcome.

Perhaps a significant part of the problem is the church’s own self-definition. So I’d like to present a model of understanding that may be revelatory.

The Body of Christ

I’ve been thinking about the Bible’s metaphor of bodies as an illustration of spiritual community among Jesus followers. I’m sure this passage is quite familiar to most believers, but let’s consider 1 Cor 12:12-27:

12 For even as the body is one and yet has many members, and all the members of the body, though they are many, are one body, so also is Christ. 13 For also by one Spirit we were all baptized into one body, whether Jews or Greeks, whether slaves or free, and we were all made to drink of one Spirit. 14 For also the body is not one member, but many. 15 If the foot says, “Because I am not a hand, I am not a part of the body,” it is not for this reason any the less a part of the body. 16 And if the ear says, “Because I am not an eye, I am not a part of the body,” it is not for this reason any the less a part of the body. 17 If the whole body were an eye, where would the hearing be? If the whole were hearing, where would the sense of smell be? 18 But now God has appointed the members, each one of them, in the body, just as He desired. 19 And if they were all one member, where would the body be? 20 But now there are many members, but one body. 21 And the eye cannot say to the hand, “I have no need of you”; or again the head to the feet, “I have no need of you.” 22 On the contrary, how much more is it that the members of the body which seem to be weaker are necessary, 23 and those members of the body which we think as less honorable, on these we bestow more abundant honor, and our less presentable members become much more presentable, 24 whereas our more presentable members have no such need. But God has so composed the body, giving more abundant honor to that member which lacked, 25 so that there may be no division in the body, but that the members may have the same care for one another. 26 And if one member suffers, all the members suffer with it; if one member is honored, all the members rejoice with it. 27 Now you are Christ’s body, and individually members of it.

How many times have we heard a local gathering of believers called “our body” or “our church?”

For the purposes of this discussion, I’m going to be very careful in using certain words, because they’ve become so deeply laden with meaning that it’s sometimes easy to miss underlying concepts. So for the rest of this discussion, I will never use “church” to mean “a local group of people who meet together in a building on certain days of the week.” Instead, I will use words like “assembly” or “gathering” to refer to these localized expressions of Christianity.

- When I do use “church” to refer to Christians, it will have a capital letter, Church, to explicitly refer to the global Body of Christ, the sōma Christou, those humans who are attached in some way to God’s kingdom.

- I will refer to “church” in specific instances (such as “cell church” or “church growth”) with quotes to identify a specific cultural term which is relevant, but the quotes will make it clear I’m referring to the term.

- When referring to the modern cultural incarnation of Christian fellowship that we find represented on so many street corners, I’m going to use the word “churchianity” as a pastiche of “church” and “Christianity,” somewhat tongue-in-cheek but also as a very intentional critique.

One thing I’ve observed in modern churchianity is a strong tendency for each local assembly to consider itself to be a fairly self-contained unit. Even those assemblies which are part of a larger community of like-minded assemblies, such as Roman Catholics or Presbyterian USA or Southern Baptists or Episcopals, and have some allegiance and formal membership with other such assemblies, nonetheless consider themselves to have some strongly localized individuality. And certain assemblies are even more strongly independent; Southern Baptists, despite gathering together annually to discuss matters of their faith and doctrine, make a point of proclaiming their independent governance, and only describe themselves as being “in fellowship” with other Southern Baptist churches.

One prominent aspect of modern evangelical thinking is the idea behind the so-called “10-40 Window” – the region of northern latitude across Asia and the Middle East where the highest population of people “unreached by the gospel” are living. The reason evangelicals consider this important is the belief that only after the gospel has been preached to every people group on earth can Jesus return to establish His kingdom.

This, to me, seems like a fairly odd dichotomy: for the individual assemblies to be so segregated, even within fairly self-consistent groups of thought, yet longing for the day when Jesus will return to make them all one. Just to be excruciatingly clear: to me, this sounds like they want to remain isolated as long as possible, not building God’s Kingdom on earth here and now, instead expecting Jesus to make it happen instantly at some hopefully not-too-distant time. Perhaps they are hoping that their particular and unique doctrine will be proven to be the right one, and Jesus will suddenly make every other assembly ashamed of missing the mark, and bring the rest of the world into alignment with their doctrine? I really don’t think most evangelicals have ever thought this through, but from the outside, it’s a rather glaring and distasteful phenomenon.

A scripture which has been very meaningful to me for some years now, and increasingly so lately, is John 17:20-24, in which Jesus is praying for His followers, saying:

20 I do not ask on behalf of these alone, but for those also who believe in Me through their word; 21 that they may all be one; even as You, Father, are in Me and I in You, that they also may be in Us, so that the world may believe that You sent Me. 22 The glory which You have given Me I have given to them, that they may be one, just as We are one; 23 I in them and You in Me, that they may be perfected in unity, so that the world may know that You sent Me, and loved them, even as You have loved Me. 24 Father, I desire that they also, whom You have given Me, be with Me where I am, so that they may see My glory which You have given Me, for You loved Me before the foundation of the world.

This passage – along with many other verses in John and scattered throughout the gospels – fairly drips with a focus on the Church (the global group of believers) being one, united, living in unity, both with each other and also with Jesus and with God the Father.

Whether or not so many local assemblies are content to think and act as individualistic, self-centered local organizations with only minimal ties to other local assemblies, and whether or not one considers those verses in John 17 to be a major focus of the gospel, I think the picture most Christians have of the eschaton include unity. So why this painful lack of focus today?

At the time that the Epistles were written, there was no significant concept of any biological structures smaller than organs and the visible body parts. Thus, the discussion in 1 Cor 12 is applied only at the organ and limb level, talking about eyes and ears and head and feet. But the biological analogy is useful, particularly because the Church is something of a living organism, with a variety of structures with varied functions and giftings.

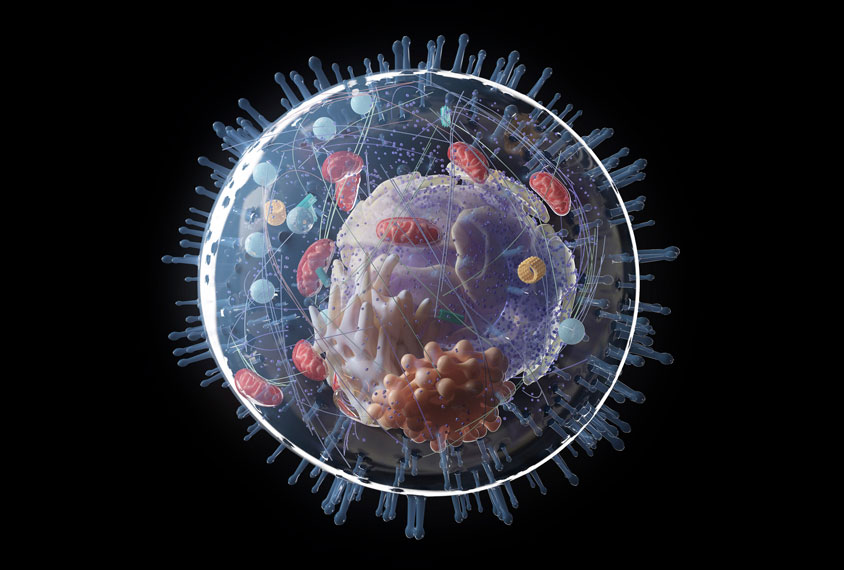

As we now know, beyond the knowledge of ancient times, the visible organ and limb structures themselves are composed of many substructures, down to the cellular and even sub-cellular level.

In light of our expanded medical knowledge, I think that we could take the 1 Cor 12 analogy a bit further, and gain some value out of the comparison.

What I see happening in the Church today is a lot of local assemblies thinking of themselves as a self-complete body, not as members of a much larger Body, the Church. Sure, they may pay lip service to The Body of Christ, and love to refer to it as if they are representative of and a part of this larger collection of believers, but what I see in practice appears rather like they would be quite content to be The Body all by themselves.

In particular, each local body – notice that I am here calling it “body” instead of assembly, because this is how each assembly views itself – each body has its own cadre of the “five-fold giftings” to meet all of their own needs, and they act as independently as one might expect an individual human body to act. As I noted above, even when they notionally consider themselves part of a larger gathering of assemblies, they often still scrupulously retain their individuality.

This is not “let them be one,” as Jesus and the Father are one. Not even close.

I believe if we instead conceptualized each local assembly as a cell instead of an entire body, we might trend closer to what Jesus was praying.

The Biological Cell

A biological cell is not a single indivisible unit, nor is it an internally-uniform entity: it actually contains “organelles,” subcellular structures that have different purposes, such as the nucleus which governs cellular functions, mitochondria which provide the energy, the outer membrane which protects the cell, lysosomes which handle waste removal, and so forth. So even within a cell there are “members,” and it is not unreasonable to conceptualize the local assembly of varied believers with different giftings and strengths as a cell.

Now, the difference between thinking of a local assembly of believers as “a cell” instead of “a body” may seem like a difference without distinction, but I think that there are some critical differences that make for an important distinction.

For one thing, cells require other cells – and importantly, other DIFFERENT cells – to survive.

Aside from certain unique cases, in general, if you extract a cell from an organ of a multicelluar organism and place it apart, it will quickly die. The systems which handle food and energy distribution, sensation and response to the outside world, locomotion and interaction with the environment, waste elimination, protection from disease and infection, and so forth are all multi-cellular systems.

And these systems are each composed of generally-similar cells. A nerve cell may seem to have little in common with a digestive cell, but both need all the same organelles to support their individual life and enable them to fulfill their unique role in the organ and thus the entire body. If you thoroughly understand one type of cell, you’ll understand the vast majority of biology of any cell type – of nearly any large organism, not just humans.

However, these organs are composed of a wide variety of uniquely-configured cells. For example, although all cells contain the same organelles, the cells need to perform remarkably different functions within their respective organs, and their form and function are modified by the expression of the genetic code by their chemical and physical environments.

The Problem

So why, if these local religious assemblies typically do operate as independent bodies, would I assert that the model of an interdependent cell is a much more appropriate conceptualization?

If all of the varied-yet-similar cells in a body do not work together, and express sufficient variation to meet the variety of needs of the body, the entire body will not survive.

So it is, it seems to me, with the Church. No local assembly of believers is entirely self-sufficient. They each have a purpose within the global Church that is unique and important, and in reality they must remain interconnected with every other assembly to truly thrive.

This is markedly different from conceptualizing a local assembly as a full human body – which could quite effectively live independently, given enough resources. And so it is with these independent, individualistic local assemblies. They can, and often do, live entirely independently of their neighbor assemblies, considering themselves as entirely self-sufficient (aside from depending on God). While they may occasionally work together to solve difficult local problems, or join larger supra-regional groupings of assemblies such as denominational structures, they still conceptualize themselves as complete and capable of independent operation and health. But any assumption by a local assembly that it stands alone necessarily includes the assumption that its few (or even many) members are collectively endowed by God with every single necessary bit of wisdom, skills, and giftings, and the assumption that its own doctrine and teaching are entirely complete and self-sufficient, with nothing to learn or be challenged by other people from different assemblies.

This corporate individualism is hubris at its highest, and is particularly deadly to any action of the Holy Spirit to expand their thinking and call them to repentance from dead works and incorrect understandings.

If this individualism were true, Jesus might as well return today, because then that one local assembly comprises the entirety of the Church, and the Kingdom has been fully built.

Obviously, that is foolishness.

Consider, instead, that just as with cells, from a certain up-close view, any local assembly has roughly the same components: the five-fold giftings are supposed to be present and operating within each fellowship. But from even a slightly broader view, each local assembly will be uniquely configured, and will have a somewhat different purpose. Zooming out a bit further, the regional gathering of local assemblies will probably have an overarching common purpose, despite their variety – and that variety lends to the common purpose. And at the denominational level, each mega-group of assemblies has a drastically different flavor, and presumably, different purpose. This is much the same way as a body’s organs such as kidney and bone and eye and brain each have very different functions and are each composed of cells, but each have their own purpose in sustaining the overall life of the body.

And this idea is reflected many times in scripture, as in the various Epistles different city churches are recognized for their own specific character, and then in the first few chapters of Revelation, are both celebrated and then challenged for their uniqueness. In fact, in Revelation, Jesus commands John to write to the angel (or more accurately the messenger) of each assembly. We tend to read the beginning of the statement to each “church” like this: “To the angel of the church of the city.” But the word for “church” here is ekklésia, which is more simply an assembly or a congregation. It’s a local assembly, not “the body” or sōma in Greek – it’s not The Church. And in fact this highlights something important: that the ekklésia or the assembly of saints within a city was considered a single unit, not a lot of individualistic synagogues. These verses do NOT read “to the angel of the churches of the city.” It’s not plural, it’s singular.

It’s probably important to note here that in the original conception of the New Testament church, elders and deacons operated at regional, city-wide scale, not within a given synagogue or house gathering. The modern concept of each assembly having its own structures and leadership is much more recent than the early Church.

Consider that from 2022 US Religion Census data in my local county, with about 115,000 inhabitants, some 50,000 individual attendees of Sunday morning services, and 88 unique fellowships that hold Sunday morning services in a building of some kind, the single largest ecumenical gathering designed to facilitate relationships between these fellowships has a paltry 14 member organizations serving under a couple thousand attendees. This demonstrates a studied rejection of intentional city-wide gathering of the Body of Christ.

https://www.usreligioncensus.org/node/1639

In some sense, then, what we see today in modern churchianity is each local assembly acting and thinking of itself as if it were a city-wide structure in Acts, and rejection of a Kingdom-wide focus. It makes each local assembly an entity unto itself, with little real responsibility to the larger Church. That should not be.

Reframing the Discussion

So here’s the big picture: if each local assembly, each ekklésia, conceptualized itself as a cell, instead of a body, a sōma, it’s likely that their sense of interdependence would be strongly enhanced.

- Instead of looking at themselves as self-complete, they would recognize that they cannot survive in isolation.

- Instead of seeing their partners as only those exactly like themselves, and essentially ignoring those next-door neighbor assemblies of different denominations, it’s likely they would recognize that interdependence with others in their local area was necessary to truly thrive.

- Instead of seeing their differences from other local ekklésia as problematic, it’s likely that they would recognize the value in diversity, in fulfilling the larger purpose of The Body of Christ.

- Instead of focusing on growing their “sōma” they would be more inclined to think of how to expand the network of small, tight-knit, well-functioning ekklésia that separately gather together on a Sunday.

- Instead of imagining many discrete sōmas, one on each city street corner, they might instead be reminded of the One Sōma of Christ, a single corporate body arising out of the whole of humanity.

- Instead of focusing primarily on what causes their imagined complete and independent sōma to thrive and grow – often at the expense of other local ekklésia – they would begin to think of what was necessary for the overall Sōma of Christ to thrive and grow.

- Instead of competing for resources – in the form of people and tithes – against other local ekklésia, they would welcome any who arrived, bless any who left, and be more committed to the Sōma Kingdom instead of their own fates.

In the book “The City Gate” (https://amzn.to/3xN6OI7), John Alley presents a vision of city churches, and some really solid reasoning for why it is so important for Christians to think city-wide instead of individualistically. Starting from scriptures, he explains how a city-wide approach provides a spiritual covering over the city – even the entire region beyond the city – while an individualistic approach opens the city to spirits of division and competition. Even if you don’t believe in spiritual warfare (many Christians do not, after all), the changes in thinking and behavior between these two approaches will definitely have effects in how the local expression of the Kingdom of God grows and functions.

To summarize, then, what I’m proposing is that the Church needs to shift its mindset from conceptualizing and referring to local assemblies as “bodies” to instead thinking of themselves as “cells.” This change would continually emphasize the interconnectedness and de-emphasize the autonomy of each local assembly.

Definitely Not “Cell Church”

In the mid to late 1990s in an assembly I attended for many years, there was a temporary emphasis on a concept called “cell church,” based upon a very large assembly of believers in South Korea led by David Cho, which modeled the entire local assembly after biological cells, which naturally experience regular “mitosis” or cell division, so that their numbers steadily multiply. In such a model, these local assembly small groups similarly multiply and bring increasing membership and expand the reach of the assembly into its community. A thorough discussion of this model can be found at

or

https://joelcomiskeygroup.com/en/resources/phd_tutorials/en_prp_yfgc/

and a simpler summary is at

https://joelcomiskeygroup.com/en/resources/cell_basics/en_cellchurch/

Theoretically, this model of “church growth” was designed to prevent the stagnation and insular nature of many small groups which operate under the covering of local assemblies; these small groups too often become cliques and tend to be hard for outsiders and newcomers to join, and thus don’t do a good job of reproducing or expanding.

But in retrospect, with the clarity of hindsight, our assembly’s experience was deeply painful, because the forced emphasis on “multiplication” (nobody was allowed to call it division because they wanted to focus on the positive aspects) actually broke up a lot of very healthy and strong and deeply-committed groups and functionally severed many long-standing relationships. Perhaps it would be easier for a new local assembly to adopt this model, but it proved to be deadly to our established assembly, and thus the well-intended change resulted in the total breakdown of the small group ministry that never did recover even after about 20 years.

This “cell church” model is markedly different from the organic approach I am discussing, that of understanding the Body of Christ as composed of cells, and I don’t think they should be confused. In particular, I see some areas of distinct harm in the “cell church” model, and I want to explicitly avoid any connection between the ideas that I’m discussing and that system, even though the overarching language is very similar.

- For one thing, I’m convinced that the focus on growth of a local assembly is deadly to the larger Body of Christ; I believe that the evidence shows that “church growth” focus commercializes the Gospel and creates some significantly harmful secondary effects which are worth discussing separately, and about which I wrote previously in “Billions and Billions Served” (https://crucibleofthought.com/billions-and-billions-served/). Instead, a focus on deep and strong discipleship is dramatically different, and is ultimately far more effective for the Kingdom, as I wrote about in “Exponential Christianity” (https://www.crucibleofthought.com/exponential-christianity/).

- For another thing, that model of multiplication (or really, division) – the way that “cell church” division regularly drives people apart in an attempt to drive growth – is ultimately harmful to small tightly-knit relational groups that form the heart of effective and vibrant assemblies, whether religious or not. And I don’t believe that any local assembly can truly thrive as a true cell in the single corporate Body of Christ without vibrant small groups, those ‘organelles’ within the cell. In fact, from my perspective, the small intimate group is far more valuable than the parent organization at furthering the goals of the Kingdom of God, as I wrote about in “Small Groups and Synagogues” (https://crucibleofthought.com/small-groups-and-synagogues/).

- Finally, the “cell church” model focuses heavily on development of powerful and effective leadership, which it considers necessary for each cell to thrive and for the parent institutional organization’s collection of cells to operate effectively. The “cell church” meeting structure was very tightly controlled and focused and it required strong leadership to stay on track and further the goals of the parent institution. While having leaders is important for any organization, I strongly dislike the inherent resulting thinking that someone needs to be “in charge” of, or in authority over, a small group. The further away from evangelical thinking I find myself, the more I see that a focus on structure and authority leads to both toxic leadership, and harmful subservience to leadership. This problem in fact exists across all of Christianity today, evangelical or mainline or orthodox. What we see happening across American Christianity is an explosion of spiritual abuse – and it’s not that the abuse is new, it’s that it’s finally coming to light and being named for what it is. I believe it’s a natural tendency of some humans to crave power and authority and control, and for other (broken and wounded) humans to crave being controlled. Both are deeply harmful. And so the “cell church” model’s glorification of strong leadership inherently provides fertilized ground for abusive and subservient thinking and actions.

I do see a few good ideas in the “cell church” model.

- For one thing, I appreciate the “cell church” idea that the Sunday morning experience is not where the true life of the Church exists. This is appropriate and I believe quite valuable. As in the first few decades after Jesus, where the Jewish synagogue model continued to exemplify the meeting practices of the nascent church, there was a marked difference between the vibrancy of small groups of believers living and eating together, and the Temple experience where they periodically joined to celebrate. The command to “not forsake the assembling of yourselves together” in Hebrews 10:25 was never about a Temple meeting; it was always about the intimate deeply-relational synagogue life. And the “cell church” model definitively promotes this idea that the life is in the cells, not the institution.

- For another, the idea that the ministries of the Kingdom ought to be carried out at the small-group level is useful – it keeps the focus of each believer on what they personally can do in their own sphere of influence, instead of pushing that responsibility up to a large multi-hundred-member organization where it can be safely ignored by most of its members. As I describe in “Billions and Billions Served,” we need to get away from “McDonalds’ Christianity” where the organization is trusted to do the important work, instead of every believer. Ministering in a small group requires personal involvement.

So stepping away from “cell church” and back to the larger discussion, when we look at this whole experience of the Kingdom of God organically, what I believe we should be seeing is a single Kingdom-wide Body, composed of organs with different functions (the denominations and people groups, if you wish), each composed of a variety of cells (the local assemblies) composed of a variety of similar organelles (the small groups within that local assembly) composed of individual believers.

Where Now?

So where do we go now? It should be obvious that I’m of the strong opinion that the current churchianity model is deeply problematic and spiritually decaying as a result. But I’m not of the opinion that the institutional religious system in America (or elsewhere) will ever largely change its patterns. There are too many people too deeply invested in that model to even see its brokenness, or be willing to lay aside their personal power and authority within that model, or to want to “rock the boat” of their own local assembly in hopes of changing its underlying structure so deeply.

But what I see across our American culture today is increasing numbers of people who consider themselves faithful followers of Jesus who nonetheless have rejected traditional or institutional Christian community models. They may show up from time to time in a local gathering, but without significant commitment. They recognize many of the harms upon which I have touched above, and although they continue to crave the connection and spiritual benefits offered by a healthy local assembly, they are disinterested in returning to those damaging structures.

So I don’t think the existing system can be changed substantially, although I expect that it will steadily continue to wane in cultural influence over time, much as has happened for a few generations in Europe.

But I don’t think that the European experience is a necessary outcome.

I believe the only path forward is essentially a path backward. That may sound suspiciously like many “make churchianity great again” proponents arguing for a return to strict legal enforcement of Christian values to restore morality to culture, some variant of Christian Nationalism, but I do not mean that in any way.

Rather than legislating behavior, which was exactly what happened when Constantine institutionalized the church under state control (largely in an attempt to use the church to strengthen governmental control over the populace with religion providing an eminently useful tool), I believe it is necessary for faithful believers to simply model something different and let the culture see it happen, see its indisputable benefits to its practitioners, and be inspired to say as in Isa 2:3 “Come, let us go up to the mountain of Yahweh, to the house of the God of Jacob, that He may instruct us from His ways and that we may walk in His paths.” And that will happen when this remnant of exiled believers from “institutional church” start acting differently, joining together in small gatherings, eschewing control and power and authority and titles, and simply living and learning about God together.

City-Wide Deacons and Elders

What about deacons and elders? After all, as the early church grew, it rapidly became clear to the believers that some roles were important. What were the reasons for these roles? Are they still valid today?

Yes, but it is critical to read the Bible’s instructions about these roles in their proper context.

Regarding elders, note that in Titus 1:5, the author writes “For this reason I left you in Crete, that you would set in order what remains and appoint elders in every city (or town) as I directed you.” Not “in every ekklésia,” every group that met together, but instead in every geographical region of believers.

Similarly, in Acts 6:1-6, the original assignment of just seven deacons was to designed serve the physical needs of the growing body of believers across the entire city of Jerusalem – many thousands of believers across dozens of synagogue-sized fellowships.

In context, then, it’s vital to recognize that this strong vision of a city-wide family of believers in Jerusalem did not conceptualize itself as a bunch of independent bodies, each with seven deacons, but as one Church, one body, under one leadership (of Christ), with workers and ministry roles held in common.

As with “returning to the early church,” I don’t reasonably see that a significant number of modern local assemblies would look at this Acts model and agree to surrender self-governance and eliminate all their individually-assigned deacons and elders. Too many people are invested in having titles and holding power and authority.

So what, then?

Moving Ahead

I believe the only reasonable way forward is starting from scratch, not converting existing institutions. The exiles need to join together to form new, non-institutional gatherings, and basically ignore whatever the institutions do or think about it.

Will there be enough people to make this work? I firmly believe so. There are plenty of people who have abandoned traditional institutional groups, and are yet longing for holy relationship. Consider the sheer scale of the depopulating of traditional American institutional religious assemblies. Consider that in 2000, 32% of America’s 282,000,000 citizens – about 90,000,000 individuals – were weekly attendees of local Christian assemblies. By 2022, that number had fallen to about 20% of 338,000,000 citizens, or about 67,000,000 individuals. That implies to me that there are some 23,000,000 Americans disaffected with American “church” practices. Spread across America, any given town will have hundreds to thousands of such people. Certainly some have entirely written off Christianity, but I believe most of them would return to the right situation.

https://www.churchtrac.com/articles/the-state-of-church-attendance-trends-and-statistics-2023

But what those disaffected people don’t have, right now, is any options that appear viable and worthy of their attention. I truly do believe this is a matter of “build it and they will come.” More than build it, perhaps, “start it and they will come.”

But it’s not enough to simply start meeting. That would just recreate the broken system all over again, as people attempt to recreate the only thing with which they are familiar. This effort to start anew requires something different.

- It’s the organic formation and organization and coming together of different, cell-thinking groups of believers, starting completely independent of any existing organizations or denominations.

- It’s being intentional to avoid the symptoms of empire that have so deeply infected churchianity, by finding useful and meaningful ways to continually remind each other as we gather that thinking like institutions and empires is what got the Church into the current situation, and it will require continually rejecting those practices and modes of thinking from this point forward.

- It’s deliberately rejecting growth as a goal. Growth is good – but the focus on growth is harmful, and there are plenty of other existing organizations happy to serve anyone who wants to focus on growth.

- It’s deliberately rejecting denominational tribalism. This may be the hardest sell of all, because each one of us has some pretty solid existing ideas about what constitutes “being Christian,” what is acceptable doctrine (orthodoxy), and what is right practice (orthopraxy). This doesn’t mean that every group needs to be infinitely diverse. That won’t work, and would cause internal trouble. But what it DOES mean is that any given group needs to be continually reminded that other groups are vitally important even if they seem “heterodox” or “heteroprax.” God will sort these matters out, and we need to be vastly more humble than we have been about these matters.

Ironically, this new model would be so different from anything presently visible in churchianity today that it would be just as countercultural in America as the Christian Church was among the Jewish people in Jerusalem beginning in Acts 2. That new Church quickly saw explosive growth, as the people of Jerusalem saw something they’d never seen before, something vibrant, something passionate, something deeply attractive. It was so countercultural and so disruptive to the established religious institutions that it wasn’t long before the institutional leaders were arresting and killing the Christian leaders in an attempt to shut it down. I’m not attracted to trouble, but at least it would be a sign that something was going right.

The Need for Tribe

But speaking of tribalism, we cannot discount the deep psychological need in most people for having a tribe, a group they can call their own, which provides some deep perceived safety in numbers, some assurance that those around them affirm their thinking and actions. This is what leads to things like denominational affiliation between local assemblies, even if (as in the case of the Southern Baptist Convention) each member institution maintains its absolute independence. We simply NEED this mutual affirmation, most especially when we’re talking about matters of faith and our need to be certain of our soul’s fate. Having something we can call “our denomination” is a powerful comfort to our souls.

Is this inherent desire for tribalism in conflict with an organic cell-thinking assembling together of ourselves into one Body?

I don’t believe so.

For all of the language in the Bible about Christians being one with each other, even a cursory look at Jewish culture shows that absolute uniformity never was and never has been a goal of the Hebrew faith. Quite the contrary: the average Jewish theologian deeply values dissent and dialog and difference. To the view of the average individualistic western thinker, there is a shocking lack of concern about uncovering and slavishly abiding by some singular Truth. But it’s not that there is no concern about truth; rather, there is a lack of concern over forcing others into alignment with one’s own ideas about that truth. There is a deep-seated comfort with curiosity and dispute.

This is a hard sell for most western thinkers, strongly affected by the Age of Enlightenment and the concomitant idea that there is One True Answer to any given question, that if we only search and reason long enough we can uncover that perfect answer to anything we consider.

But that idea is alien to many modern non-Western thinkers, and would have been alien to anyone in Biblical times. So maybe it’s something we Westerners need to adjust in our thinking.

This doesn’t prevent choosing to join together in deep fellowship primarily with those who tend to agree with us. But we must avoid toxic tribalism, where we use that membership to make “others” of those who are unlike us, to hold them at arm’s length, to reject their faith or even their humanity.

For all the angry diatribes and demonization leveled by conservative Christians at liberal or progressive Christians, I think the most misguided is this: that progressive or liberal Christians are too inclusive, are too willing to accept any thinking or doctrine or behavior in the name of peace and acceptance. Yes, inclusivity can be taken too far. But I am finding that, on balance, the damage of exclusivity is far worse, especially when we wish to model the character of a God whose self-revelation is consistently about measureless love and unfailing mercy that confounds human conception.

Given that inclusivity, I think this organic model of Christianity must necessarily start from a place of studious rejection of tribalism, a rejection of a distinctly toxic “othering” of those with whom we disagree. Only from a starting place of anti-othering can we truly begin becoming one.

If we want to do it right, we might recall Jesus’ parable of the wheat and tares in Matt 13:24-30, where Jesus said:

The kingdom of heaven may be compared to a man who sowed good seed in his field. 25 But while his men were sleeping, his enemy came and sowed tares among the wheat, and went away. 26 But when the wheat sprouted and bore grain, then the tares became evident also. 27 The slaves of the landowner came and said to him, ‘Sir, did you not sow good seed in your field? How then does it have tares?’ 28 And he said to them, ‘An enemy has done this!’ The slaves said to him, ‘Do you want us, then, to go and gather them up?’ 29 But he said, ‘No; for while you are gathering up the tares, you may uproot the wheat with them. 30 Allow both to grow together until the harvest; and in the time of the harvest I will say to the reapers, “First gather up the tares and bind them in bundles to burn them up; but gather the wheat into my barn.”’

We have to be willing to let what we consider weeds and tares grow alongside what we consider valuable, and let the reapers sort it out at the end, not aggressively attempting to fix the problem ourselves. Clearly the landowner was not concerned that the weeds would significantly affect his crop, and perhaps we would do well to stop trying to root out what we see as heterodoxy or heteropraxy, lest we do far more damage to the crop ourselves.

What About Leaders?

In view of gathering many possible doctrines and beliefs and worship styles and expectations under one roof, one might then reasonably ask about leadership in this organic, cell-thinking model of Christian community. Who should we expect to resolve issues between members of such a group? Who will set the direction for a group?

I see two problems with this question itself.

One, it presumes that there is someone best able to hear the voice of the Lord in such a situation. Two, it presumes that this person is a healthy and safe leader.

In the last few years, America has seen a stunning array of scandals involving Christian leaders of various institutions, and of the institutions themselves. Consider the Southern Baptist Convention, which in 2022 was confronted publicly over its failure to reign in and disfellowship scores of sexually-abusive pastors and leaders about which the leadership had long known. The Guidepost Solutions group collated an extensive 205-page document detailing over seven hundred credibly-accused sexual predators in top leadership positions within SBC member assemblies. You can even read the list for yourself, knowing that it just scratches the surface and only addresses those abusers who were specifically identified in court cases, and doesn’t touch those who avoided legal trouble by virtue of institutional sheltering.

https://www.classlawgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/SBC-List-of-Alleged-Abusers.pdf

Or consider the long-running Catholic clergy sexual abuse scandal, which has rocked the Catholic denomination for well over two decade with over six thousand credible accusations.

https://www.abuselawsuit.com/church-sex-abuse/

Another list of older religious scandals up through 2008 details many very high-profile leaders which fell from grace.

https://en-academic.com/dic.nsf/enwiki/118212

Why does such a horrible record of abuse exist across institutional Christianity?

The answer probably starts with the way that religion (in general) has a long history of giving its leaders great power and responsibility over the members of their assemblies, reinforced using threats of retribution by the deity for those who resist. This ingrowth of empire into religion is very natural to humanity; there are always going to be people who crave power and authority over others. And in the case of Christianity, unfortunately, this comes with a wide array of verses often used to teach submission to all authority, especially religious authority – verses like “touch not the Lord’s anointed” in Psalm 105:15, or in Romans 13:1-2, which says “there is no authority except from God, and those which exist have been appointed by God. Therefore whoever resists that authority has opposed the ordinance of God; and they who have opposed will receive condemnation upon themselves.” These and similar verses are used to suppress dissent and drive compliance, often by toxic leaders arrogating power to themselves.

This is not to say that leadership and authority are inherently invalid or wrong. They are not.

However, a claim that leadership to set direction and resolve disputes is an essential component of a Christian assembly misses an essential feature of the Church which was instituted by the Holy Spirit following the resurrection: the universal priesthood of believers. There is a fairly explicit understanding in the New Testament that each believer is able to hear the voice of the Lord and respond to it, and that each believer is granted a measure of authority in the spiritual realm.

Furthermore, in the post-Jesus Church, there is a fundamental expectation of the equality of believers. The believer’s authority is not over each other. The model is no longer of a priest who is the go-between from God to man, or a liturgical leader managing the flow of a worship service. Instead, the explicit understanding of the young Church was that each member would contribute in each meeting, as in 1 Cor 14:26, “When you assemble, each one has a psalm, has a teaching, has a revelation, has a tongue, has a translation.” The spiritual giftings that are instituted in the “five-fold ministry” model are not meant to provide leadership, but instead to provide the skillsets within the ministry to bring about maturity and health of the members. It’s only the brokenness of the modern assembly that expects these five-fold ministers to take charge – in fact, often converging in a single human, where the ministries of pastor and teacher and evangelist and apostle (the visionary) and prophet (bringer of correction) and furthermore the business leader of the local assembly are typically all expressed in a single pastor or priest who leads and directs the assembly.

In any event, in a situation where a dispute arises, why would we assume that one person is better suited than another – or than the collective group – to hear the voice of God for the group? I suggest that it’s a cultural expectation, more than a Biblical one. We want a “strong man” to set the course, and take charge of difficult situations. But what is probably more Biblical, if anything, is for each person involved to participate in whatever governance the group requires. No one person should be less than any other; no one person should be more than any other. Plenty of verses address this essential aspect of Christian relationships, the self-sacrificial humility modeled by Jesus: verses such as Romans 12:3, Gal 6:3, James 4:6, and perhaps the most potent passage in Phil 2:1-11, the concept of kenosis, the emptying of self for the benefit of others. In such an environment, fully realized, there is no need for a strong man; the corporate man standing together is able to make all righteous judgements. The system only breaks down when people abdicate this role to a strong man – who is then able to abuse them.

Note that the original design of God’s people in the Hebrew Bible was not kingship, but dispute resolution and leadership at a much lower level. It was only when the people rejected God’s model that God relented and granted them kings – along with a stern warning of the bad fruit this would bring. And the subsequent history of the Hebrews bore out the truth of this warning. Strongman leadership is generally toxic.

Again I point out that these single-strong-leader expectations are very cultural and deeply baked in to modern churchianity, and it is unlikely that any existing assembly would abandon them. I raise these points to emphasize that an organic cell-thinking small group needs to avoid these traps as it assembles and organizes itself.

A Different Leadership

With this de-emphasis of strong and individualistic leadership within a cell-thinking group, one might ask how any given local assembly could be appropriately fitted together, and how the Body of Christ could possibly be properly arranged. After all, the organs and limbs of a physical body need headship to motivate and guide them. While Jesus is understood to be the ultimate head of His Church, such global Church-wide government might nonetheless be expected to include a human element at the highest level. The word “apostle” is defined by Miriam-Webster to mean “a person who initiates a great moral reform or who first advocates an important belief or system.” In the Biblical context, the Greek term had a strong sense of being sent. If we consider Paul’s example in the New Testament, he provided apostolic guidance and inspiration across a huge region, while generally leaving each local assembly to its own devices.

There is a related leadership model being discussed these days, often called “spiritual fathering” or “spiritual sonship,” which is quite different from denominational power structures or from one-man pastorate leadership. Over the centuries there have been plenty of toxic examples of men claiming to be a father or patriarch over large spiritual groups. In the 70s and 80s there was a surge of interest in very patriarchal “apostolic” churches, where the strongman in the church was called an apostle. But note that “being sent” implies non-local leadership – as one who promotes the beliefs of the system across great distances. It would be strange to think of an apostle solely of a single gathering. Many Christians were harmed in these movements by strongmen who abused their local authority, and the term is not in favor especially with those who have left traditional institutional Christianity.

But there may yet be some good models of effective leadership that would serve well within an organic cell-thinking ministry model.

In particular, there are many thinkers about the topic of spiritual sonship. Speaking of sonship instead of fatherhood or apostleship inherently puts the emphasis on the recipient of the leadership, instead of glorifying the leader.

Dr. Sam Soleyn is one of those thinkers, with whom I am intimately familiar. He has written numerous books and recorded hours of teaching on the subject. One unique aspect of his model is that while it does use the terms “father” and “son” he explicitly emphasizes that they are not gendered terms; there is no room in his model for gendered patriarchy or toxic complementarian thinking. He uses the word “patriarchal” but only in the sense of the senior parent of a large household composed of families each with their own parents, not just of male leadership. Nonetheless he retains the terms “father” and “son” simply because they are used in scripture and thus speak clearly to many people.

The organization proposed by Dr. Soleyn is based on the idea that God’s spiritual family will be composed of local families, organized into households, which are then ordered into tribes, which are ultimately ordered into nations. Naturally, all of this organization is submitted to the headship of Christ, at every level.

A key aspect of Dr. Soleyn’s model is that it is never coercive, and it initiates at an entirely relational level when both parties recognize an existing bond created by the Holy Spirit. It inherently includes accountability both from father to son, and upwards from son to father. The father is not necessarily older – just more spiritually mature. And the specific and overriding focus of each father or parent is to bring about maturity in those under their care, to reproduce that maturity in the sons, so that each generation is raised up and advanced beyond the parents’ own maturity and ability. It is never meant to bring honor or glory or wealth to the patriarch – the leader always rules for the benefit of those that they rule.

I find Dr. Soleyn’s model to be the most convincing of what could appropriately serve what would otherwise look like an anarchical collection of cells without any structure. That would be an ineffective Body of Christ, each accountable only to itself. Some form of governmental structure seems necessary.

Can such a spiritual parenting model as envisioned by Dr. Soleyn be corrupted? Certainly. But in my sense, it’s the least likely to be corrupted of all the various models I have observed so far. Abuse of any kind seems to require control as a key enabling feature, and Dr. Soleyn’s model eschews control. Instead of “do what I say,” the focus is “watch me walk with the Lord, and do what you see me doing, and I stand ready to assist you in becoming more like Jesus; if I see the need for correction, I will offer it with an open hand instead of a demand.”

Dr. Soleyn is clear that this governmental model is less about regulation and more about the economy of the household of God. The Greek term oikonomos is source of the English term “economy;” it is a compound word from oikos, household, and nomos, arrangement or management or law. Thus, the economy is the engine which drives and motivates and organizes the family. In any human system, the economy is the sustaining force, enabling all good activity underlying it and allowing it to grow. God is thus establishing provision and order for the household, more than merely ruling it.

Given that Dr. Soleyn has written and spoken extensively about his conceptualization of the proper ordering of the Body of Christ, I will refer you to his writings found on the “Books by Sam Soleyn” page starting here:

https://www.mrowl.com/branches/samsoleyn

Of his books, “My Father! My Father!” is an excellent starting point, and freely downloadable ebook and PDF copies are linked on his site, as well as a Kindle version available for just two dollars on Amazon.

I do recognize that a great many Christians have been badly wounded by toxic institutional systems and leaders, and that many of those who have walked away from institutional Christianity will want to avoid any semblance of control or leadership. I have heard the cry in response, “we will have no king but God” (quoting Thomas Paine in 1776). This is very understandable, and I desire to honor such pain and trauma. In such cases, as these cells form, I see no reason to impose any guilt over a determination to avoid external leadership entanglements.

However, I’m nonetheless of the opinion that there is ultimately a deep value in being part of a larger well-ordered structure. Just as I argue above that it is unhealthy for a local assembly to consider itself to be an independent “body” instead of a cell in a much larger body, I think these otherwise-independent cells would risk much of the same trouble, even if they think of themselves with the humility of being a small part of a much larger body. But given that most of the early participation in a model that I am proposing would be coming from refugees and exiles from traditional institutional congregations, I expect that many of these “cells” would only slowly adopt any kind of assembling into larger governmental structures. And as with many other things in my current understanding, I must be okay with whatever structure other believers can accept, and at whatever pace they can adopt it.

I firmly believe that as people gather organically, and see the goodness of God reflected in these new structures, healing will occur, and appropriate family- and tribe- and nation-sized models can be constructed. And, much as each cell-thinking assembly will be unique (and that’s okay), I believe that the related connectivity to the larger body will be unique (and that’s also okay). One essential point of this organic model is that although any given cell has much in common with any other cell, the diversity between cells and organs is part of the strength and should be celebrated, not fought.

Conclusions

I’ve certainly covered a lot of ground here. I think these are the core points:

- The current widespread model where a local institutional Christian assembly conceives of itself as a standalone body is both broken and unscriptural.

- The organic model of the Church as expressed in 1 Cor 12:12-27 can be expanded to explain that any individual assembly might be best conceptualized as a cell in an organ in the Body of Christ. Individual believers are not the cells in this model: the assembly is the cell, and the individual believers would be represented perhaps by the “organelles” in a biological cell.

- Cells need each other and they need variety, in ways that individual bodies merely working together cannot provide.

- This organic understanding of cells as the foundational unit of the organization of the Church is not the same as “cell church,” although there are some similarities.

- It’s unlikely that the existing churchianity can be converted into a more organic cell-thinking structure.

- The best path forward is likely starting from scratch, reclaiming those lost to institutional church by demonstrating a better model.

- Any fellowship of believers that wants to lean into this model must be determined to be comfortable with variety of structure and doctrine and purpose, and resistant against those who would take charge over others.

- There are viable models of governmental structure within the Body of Christ that may serve in this organic system, without depending on toxic leadership systems. I suggest that Dr. Sam Soleyn’s thinking on this topic is helpful.

I hope this thinking is useful. In the end, whether or not the Church can find its way out of the toxic leadership systems and hyperindividualism common to Western culture, it seems obvious to me that the decline in membership of American “churches” is likely to steadily continue if not accelerate. I believe the decline is not due to spiritual attack, but rather a direct call of the Holy Spirit to “come out of her” as in Revelation 18:4. It seems to me that God is directly winnowing the Church, sifting out a lot of dead and useless chaff, and the institutional model across Western culture has been found deeply wanting. As such, the exilic remant must find a way forward without its familiar structures – much like the Jews displaced from Jerusalem by the Babylonian Exile had to chart a new way forward to worship God without the priests and the Temple. The new ways of being a faithful people didn’t look much like the old ways, but they were blessed by God. So it is with the American exiles from institutional Christianity. Let us recognize our losses, mourn them appropriately, but move on to the new things to which the Holy Spirit is calling the people of God.