Let’s talk about reading.

I’ve been deconstructing and rebuilding my faith for about four years now. For multiple reasons, I walked away from my former evangelical church in 2022 and have been steadily and diligently digging through all my various dogmas and doctrinal beliefs ever since.

Similarly, I started rethinking my politics about the same time – triggered by the anti-racism uproar that exploded onto the American scene in 2020, and my sudden awareness of something I’d long assumed was no longer a real issue in America.

And, wow, did my rethinking lead to some drastic changes in my life – but I’m intensely happy that it did, and I’d like to talk about it for a few minutes.

One of the immediate effects of beginning to question my long-standing beliefs was an awareness that I’d made a ton of assumptions about religion, politics, and history – and I could see, with fresh vision, that there were logical and historical holes in many of my assumptions. I needed to start looking at those topics very closely if I were to have any real understanding of them. It was no longer sufficient to me to hold rigid positions that I couldn’t back up with real facts and data.

So I embarked on a self-study program, because I knew I needed information I didn’t yet have.

I actually started with studying the history of racism in America. I should be clear that my deconstruction started with racism, not my religion, because my response to the George Floyd murder by police opened my eyes to the possibility that Black people who’d been complaining about racism in America might actually have a point.

But when I watched how my church and my denomination actually behaved, instead of merely how it talked about racism, it was my church’s unchristlike response to that murder and the nationwide upheaval that led me to realize that all the things we’d been teaching were not what we actually believed. If you don’t DO something, you probably don’t really believe in it, even if you talk a good talk.

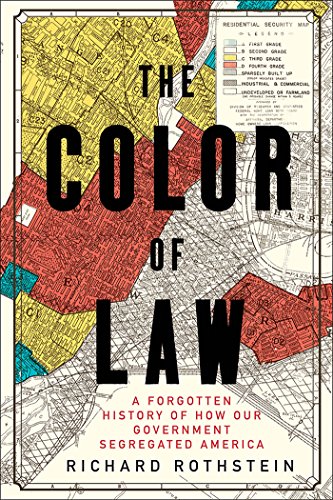

The very first book I selected – “The Color of Law” by Richard Rothstein – effectively grabbed me by the throat and shook my assumptions violently. Everything I thought I knew about racism was challenged. I’d picked the book because the author was widely lauded as careful and factual, and it was a very well-sourced book with tons of footnotes and references. And to be shamefully honest, I picked it because it was written by a white man, who I really believed meant I’d get a more accurate assessment than from what I thought was going to be a racially biased view from a Black author.

At any rate, now I was confronted with hard data, and a ton of history, that told me I’d been wrong. More to the point, I’d effectively been lied to by people I trusted were solely interested in the truth, and who wanted the best for society – and this one book proved that all wrong.

I quickly followed that book with “Uncomfortable Conversations with a Black Man”, “How to Fight Racism: Courageous Christianity and the Journey Toward Racial Justice”, “The Color of Compromise: The Truth about the American Church”, “Building a Multiethnic Church: A Gospel Vision of Grace, Love, and Reconciliation in a Divided World”, and “Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America.” And these books, unlike the first, were written by extremely well-spoken and well-educated Black men. And they unflinchingly presented a view of American history that had been very well hidden from me for decades.

Just due to the emotional import of what I had to consider, it took me 9 months to go through these 7 books, and absorb all I was learning, but by the end, I was absolutely convinced that the evidence was indisputable, and everything I’d been taught – and which I’d been telling people, and which I’d used to justify my politics – was dead wrong. Dangerously wrong. Harmfully wrong.

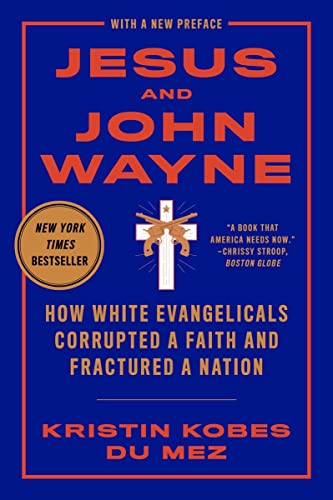

The next book I encountered changed my world forever: “Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation.”

After reading all these books about Black topics and racism, some of which touched on difficult topics of how the American church was complicit in racism, this book about white thinking was a natural next book to read. But it rocked my understanding again, because it showed, in ways that I was now finally ready to accept, how so much of my theological and political worldview were tied together by some very unhealthy features.

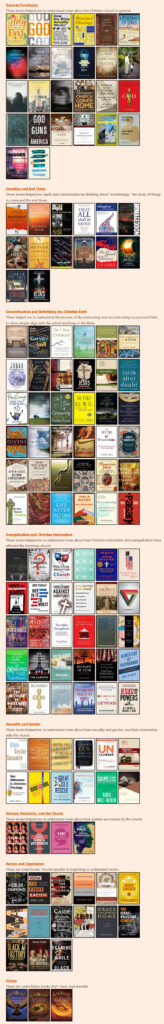

At this point, I’ll stop detailing books. By now, in early 2025, I’ve read a total of 140 or so books, all totaling about 40,000 pages. The topics have covered a huge gamut, including racism, evangelicalism, sex and gender and queer issues, eschatology, Christian nationalism, and more. And without exception, in one particular way the body of information was self-consistent, and led me to a specific conclusion: I’d been consistently misinformed, horribly so, and the foundations of my faith were misplaced – my faith bot h in my doctrine, and in my politics.

I’ve heard it said that going to seminary is very dangerous for a Christian. When I actually dig into that statement, I think it’s more true for a conservative Christian – and that’s why I’ve heard it said, because I grew up conservative. If you were raised like me, you didn’t hear much that opposed your views. But when you go to a serious religious school, you’re bound to find out that there are a wide variety of other understandings. And if the school is honest, you’ll quickly discover that each of those understandings are actually well-supported by the scriptures – even if they mutually disagree. This cannot help but induce a crisis of faith, if your faith is predicated on a simple, unchallenged reading of just one interpretation of the Bible. The more conservative or fundamentalist you may be, the more likely you’ve been warned against seminary.

So let me step backwards for a moment. Because that bears some explanation.

Growing up very conservative evangelical, and perhaps slightly fundamentalist, one of the ideas I’d inherited was a strong distrust of opposing opinions. I use the word “inherited” very carefully. I cannot think of any specific times where my parents or someone who I trusted as a leader or teacher had explicitly TAUGHT me to avoid learning, or to avoid exposing myself to alternate opinions. Oh, they’d definitely taught me to study and learn – but only from “approved” sources, so to speak.

On the other hand, I can think of many ways that the upbringing I did have actually LED to that conclusion – to avoid learning certain things. Christian songs and movies talked about the need to keep our thoughts pure, to resist the devil’s attempts to influence us, that the devil was a liar and would seek to corrupt our minds so that we would turn away from God. Examples were often made of people who had exposed themselves to alternate understandings and then backslid, who had fallen from the faith, and how they were lost to hell forever because they abandoned their first love.

And politically, growing up in a Republican household and very conservative faith community, the fear of socialism and Marxism were strongly drilled into me. Anything which smacked of “power to the people” or “Black pride” or social justice or non-traditional marriage or sexuality was deadly to America, in that view.

So, it’s not surprising that for all my life until 2021, I’d avoided submitting my mind to any information which ran counter to my dogmatic positions. I’d been carefully taught a lot of doctrine about how our denominational beliefs were the absolutely correct ones, and I’d been fed a political world view that was very strongly positioned to reject any liberal or progressive ideas.

With this in mind, why would I dare read a book that presented a cogent argument against my existing ideas? I might be swayed by seductive words and logic, and lose my faith or my political purity.

And this raises an interesting point, or a corollary if you will, to this idea of losing your faith, either religious or political. And it’s this:

Our American political system is strongly tribal. And so is our faith.

And one of the worst things you can do to yourself is to get yourself kicked out of your tribe. If you’re not sufficiently pure, you become an outsider, and then you become politically or religiously homeless, and you’re not really welcome on either side. So there’s a really, really strong pressure to stay fully and completely conformed to whatever your tribe says and believes.

But here in the 2020s, with the expansive social media world, it’s possible to become connected to a lot of other people who believe like you do – no matter how niche or diverse your own views happen to be. And because there are so many flavors of politics and religion floating around, there’s actually a fairly wide tolerance for diversity of ideas, once you get outside those highly-tribal, single-view groups on the extreme margins of the political or religious spectrum.

So suddenly, in this new connected world, you can step outside one of the bigger tribes, at least experimentally, without losing everything. And you can do so “safely” – without all the awareness or permission of the humans that you see weekly in real life. And you can do so knowing that you don’t necessarily fully agree with them any more. This gives you permission to think more carefully, and question your dogmas, without losing your social circles.

…at least until you reach the point where your ideas are so divergent from your local real-life tribe that you’re unwilling to stick around them any longer. And then you have to choose.

So back to the book thing.

Am I better off by having stepped outside my tribal bubble, and choosing to drink from a well that I’d been told was poisoned?

Yes.

Could I have stayed in the tribe forever, comfortably?

Yes.

Would God still have accepted me?

Yes.

In some ways, it feels like taking a bite of that fruit that Eve was offered, with the promise that it would open her eyes. And it did exactly, precisely what the serpent said it would do. And… it didn’t kill her instantly.

Am I arguing against myself here? Perhaps, if you believe that the story of Adam and Eve and the serpent and the tree of knowledge of good and evil is prescriptive, warning of the danger of having our eyes opened. In that case, I’m sure you see what I’m discussing as deeply dangerous.

But here’s a rather different take on that story: if you accept, as I do, that these ancient stories – some would call them myths or metaphors – are origin stories designed to explain how the world ended up the way it is, instead of factual histories. And God is presented in that story as trying to keep eternal life and expanded knowledge their sole divine prerogative, and preventing the humans from accessing it – because as God said to the divine council, “with that knowledge, they’ll be too godlike and be competing with us, and that’s not acceptable. We must cast them out of the garden, lest they live forever.”

And this comports with many other ancient stories: the gods tried to maintain their superiority over humans, and quite a few myths tell a tale of a human becoming too godlike, and the gods casting them down for their arrogance.

But here’s the thing that’s quite unique about the Bible: by the end of it, after many more stories have been told, we arrive at a place where God is explicitly inviting humanity into exactly that place: eternal life, with full awareness and knowledge of good and evil – and the Holy Spirit’s wisdom on what to do with that knowledge for the good of those around us. Our purpose, if we take the Bible seriously, is to be utterly indistinguishable from God – and to exercise God’s very power and authority ourselves.

So I’m not fearful of acquiring that knowledge myself. The story in Genesis doesn’t scare me off: instead it invites me into a place of closer relationship with God, of becoming steadily more like God, the very thing that the early depiction of God showed as a bad thing but later is shown as the actual goal of God for humanity.

But what do we do with the expanded knowledge we inevitably get by reading books that open our eyes to things we didn’t see before? Aren’t we breaking faith, or getting torn away from our simple early pure ideas?

No.

I’m convinced, these days, that God is more interested with what we do with what we’ve been able to ingest and digest, than with an absolute answer. I’m convinced that the Holy Spirit continually nudges us, trying to mature us, to break us out of our tribal dogmas, to see a more expansive view of God and our politics. But we ALL have our individual blindnesses, and many of them are too deeply rooted for us to ever fully overcome.

But I don’t think that has anything to do with our salvation.

I used to believe, with all my heart, that there was a perfect truth that I was responsible for knowing, accepting, and proclaiming, and doing so would be the cause for my salvation.

But today, my foundational assumption about salvation is that we’re subject to human limitations, and it’s utterly impossible for any of us to properly grasp the entirety of The Truth with a capital T. As such, God accepts us with our frailties – which means that God accepts us despite our limited grasp of the perfect truth. And that ultimately means that God accepts all of us.

It doesn’t mean we’re all correct. It doesn’t necessarily mean that every religion is true and “a way to God.” But it does mean that our correctness is not the basis on which we’re judged. Rather, we’re judged on those two greatest commandments, on which hang all the other stuff: love God (as best as we understand how), and love each other (again, as best as we know how).

If we get those things wrong, I’m sure some refining fire is in our future.

But I’m sure we’ll ALL get those things wrong at SOME level or another. And so we’re all going to be refined in the fire; of that I’m certain.

And that refinement, in my current understanding, is NOT condemnation to eternal pain; instead, it’s purification for entering an eternal living relationship with the God who created and loves and longs for us.

So from that perspective, I’m absolutely unafraid to read stuff which uproots my dogma. Because I trust the Holy Spirit more than I trust my brain and my understanding. That, fundamentally, is my point of faith: that God’s hold on me is infinitely more potent and trustworthy than my hold on God.

So I’ll pursue knowledge – in the words of 2 Timothy 2:15, “Do your best to present yourself to God as one approved by him, a worker who has no need to be ashamed, rightly explaining the word of truth.” Or in the old language of the King James Version, “Study to shew thyself approved unto God, a workman that needeth not to be ashamed, rightly dividing the word of truth.“

Thus, I’ll keep studying. And I’ll trust the Holy Spirit to illuminate my thinking, and to help me discern what’s worth keeping, and needs discarding. But the key is this: I’m going to read a lot of stuff I’m uncomfortable with, instead of avoiding it. Because I want the Spirit to have as much knowledge, as many “words of truth” as possible, to work with in my mind. I don’t want to stand in front of that purifying fire someday, and have to explain that I refused to repent of a false belief because I was afraid of having my mind polluted by a view that didn’t fit those existing beliefs.

And I don’t expect that to ever change. I don’t think I’ll go back – any time soon, at least – to just saying “Here I stand. I’ve settled my doctrine. I’m now correct.”

Because at the core, I’ve concluded that there is no such thing possible for me, as a limited human. I’ll never be fully correct. And so my studying cannot ever end. I’ll always be welcoming God to change my mind, just a little bit more at a time, so that I continually become closer to fully representing God than the day before.

If you’re interested in my reading list, I’ve been very carefully recording it, and writing at least a brief review of each and every book, and you can find them here under the Book Reviews tab. And if something you find there tugs at your heartstrings, I’ve included direct links to the Amazon page for each book.

Thanks for accompanying me on this wild ride. It’s both terrifying and exhilarating at the same time. And I wouldn’t have it any other way.

We’ll talk again soon.