Did God stop speaking at the end of the first century AD? Did He tell us literally everything we need to know in the Bible?

For the last three years, I’ve been stepping outside the confines of my inherited faith tradition and doctrine. As I’ve finally been exposed to some different perspectives, and observed how different groups and denominations approach the Bible, I’ve been thinking about the various basic approaches to reading and understanding the Bible. It seems to me that there are at least two spectrums of Bible interpretation methods at play, and they result in some rather different outcomes.

- One spectrum is the inerrancy scale: literal/historical versus metaphorical/myth. Are all of the events narrated in the Bible literally and precisely historical fact? Or some of them? Or none of them? I should explain that “myth” doesn’t necessarily mean “imaginary.” In this case, I use mythical to mean how stories can become inflated, or glorified, or idealized over time, such that stories that may very well have very factual roots are not factually told. It’s rather like the “inspired by real events” disclaimers you see on many historical fiction movies these days. Some liberties have been taken for the sake of telling a useful and morally helpful story. It’s not pefectly accurate but it accurately conveys the story. The wonderful movie “Master and Commander” may have only slight relation to a real historical sailing ship captain, but it perfectly conveys the struggles and fears and hopes of someone who lived in that situation.

- The other spectrum is the authority scale: prescriptive versus descriptive. Do we believe, or not, that some or all the commands and ways of living that we see detailed in the Bible are prescriptive of how we should live, or do we see some or all of them as describing how a particular set of people lived, or were supposed to live, at that time in history without also believing that they automatically apply to us?

These two aspects are somewhat independent of each other, but both are operating in each person or group.

There are certainly other possible principles of interpretation, each with their own spectrum of acceptance, and I think that would similarly operate independently of each other. I won’t be addressing them here, but some others that come to mind are:

- Changability: Static versus dynamic. A static Bible (that everything God has or ever will have to say has already been revealed in the volume we call the Bible) versus progressive scripture (that the total word of God is still being revealed). Many Mormon churches, for example, believe that God is still speaking today, and that modern revelations can join the Biblical canon after suitable review and consideration by a trusted body of Church-wide elders.

- Application: Collective versus individual. The question is whether the Bible was primarily written to and for a group, or primarily for individuals even within the group of the Church.

- Governance: Corporate versus collective authority. Who holds authority over the interpretation of scripture, whether the individual believer, or only some governing body such as the Pope for the Catholics, or a denominational assembly such as the Southern Baptist Convention, where all members must submit to the interpretation by the collective assembly or the central authority.

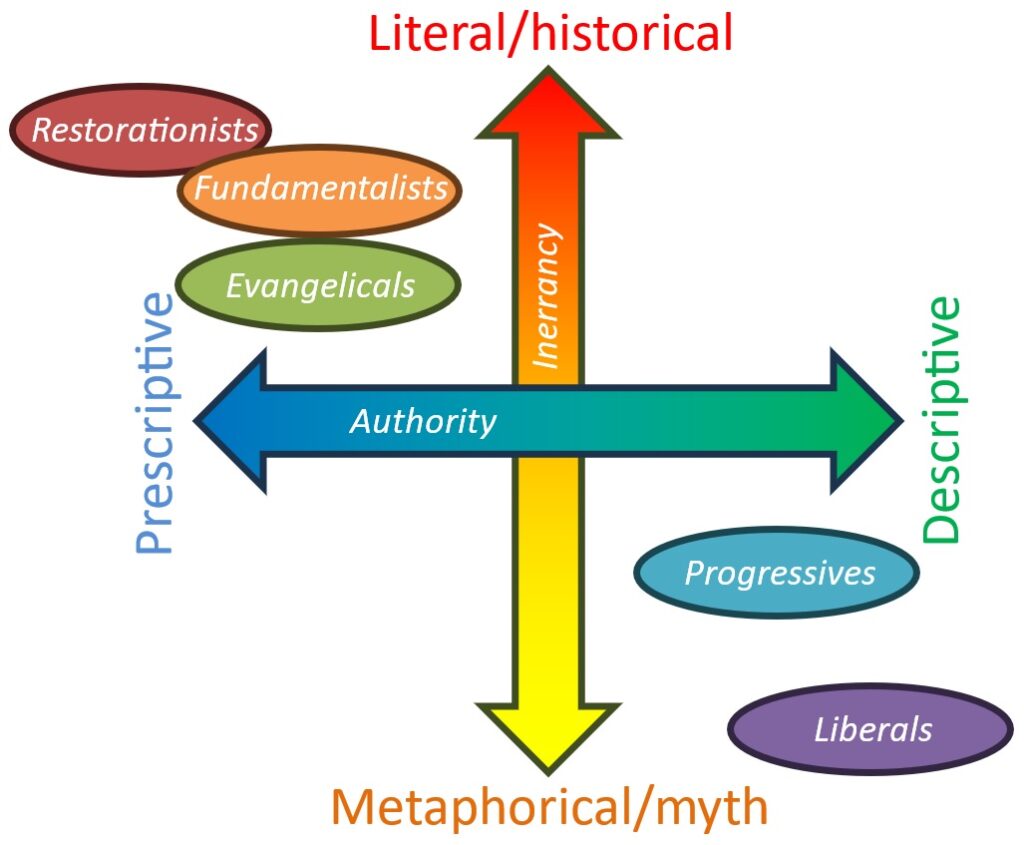

For this discussion, I’d like to consider primarily the first two: literal versus metaphorical, and prescriptive versus descriptive. Think about them, perhaps, as orthogonal axes like on graph paper. From this perspective, you could say that the extremes are represented by the corners, and moderate positions lie somewhere near the middle. This image illustrates my sense of these two spectrums or scales, and where a few Christian schools of thought lie along the axes. (This is entirely my thinking and not based on detailed study or research; I’m not a theologian or Bible scholar, and I’m not particularly invested in it, so feel free to offer your own thoughts in the comments.)

Restorationists believe explicitly in the most extreme literal/prescriptive position, way out in a corner of the graph – they believe we need to return to exactly following the Old Testament law, exactly as written (usually in the King James translation) even now in modern times.

There are Biblical literalists who believe that the Old Testament law was fulfilled (even if not nullified) by Jesus, but nonetheless believe that the New Testament is still strictly prescriptive, a less extreme position than restorationists. Many fundamentalists seem to generally take this approach, but selectively adopt Old Testament positions, such as (of course) the Ten Commandments, but more generally any Old Testament rules that support their chosen morality code.

Evangelicals generally hold strongly to the authority of scripture. Many (but not all) insist upon inerrancy – but if you poke at them hard enough, many will accept much larger portions of scripture as less perfectly historical (for example, not insisting on a literal 7-day creation).

Opposite the restorationists, and nearly opposite the fundamentalists, are the most liberal Christians, who would assert that the Bible is nearly or entirely mythical and is merely descriptive of great wisdom by which we should live, not containing any absolutes.

Progressives tend towards the liberal corner, but generally have more respect for the Bible’s authority and trustworthiness, while being rather less insistent upon them than the other prescriptive and literalist Christians.

I used to live in that literal/prescriptive interpretation realm – not extreme, but definitely close to the evangelical/fundamental corner of that graph. From that perspective, any command, or any description of God’s nature or actions, must be interpreted literally and must be fit into our framework of understanding, and the stories that described the presentation of those commands and actions and Divine nature were factual – which added much greater weight to the matters at hand. Some things, naturally, we reinterpreted as not relevant to life today (we don’t routinely stone disobedient children to death these days, for example), but we nonetheless interpreted those as having been strictly factual and absolutely prescriptive at the time they were given.

In the last year or so, I’ve begun to recognize that many things I’d believed about the Bible itself were at best verrrrrrry weakly supported, if not outright factually incorrect. For example, Jewish historical records don’t indicate that many of the more extreme commands in the Torah were ever actually followed. Or, the claim of Biblical inerrancy usually includes the disclaimer “in the original autographs” – but nobody had told me that no such original copies actually exist, and in many cases, could ever HAVE existed, since the events described in the Torah, the first five books of the Hebrew Bible and our Old Testament, purportedly took place hundreds of years before Hebrew first became a written language. Or, as another example, archeological discoveries in the Jericho area show that the stories of conquest in Genesis simply were impossible, given the complete lack of large walled cities in the area at the supposed time of those events, or that the “cities” described as being conquered by the recently-liberated Hebrews were only small villages in most cases at that time. And there is zero archeological or literary evidence for a mass Hebrew exodus from Egypt.

Somehow I have to reconcile these historical facts with my religious beliefs: I either must discount the facts, or change my beliefs. In the end, such facts – far more than I have time to recount here – forced me to reconsider my position on the literal/historical-metaphorical/myth axis.

Instead, it begins to make more sense to understand the oldest material in the Bible, to put it perhaps crassly, as family legends writ large. Or more politely, perhaps, a faithful recording of generationally-drifted stories, written down many hundreds of years after their first telling, and subject to centuries of optimizations and self-talk. It’s similar to believing that George Washington threw a silver dollar more than a mile across the Potomac River (long before silver dollars even existed, no less), or that he chopped down a cherry tree at the tender age of six and refused to lie about it to his father. Such stories tell us useful and generally true things about George Washington, yet without being completely factual.

Similarly, the Bible stories, even if I cannot believe them all to be historically factual, can and do also tell us many useful and true things about God.

Surely, goes the argument (which I personally made many, many times over decades of faith in the inerrant Bible), an omnipotent and omniscient God can ensure that His word can be perfectly recorded by fallible people. But is that necessary?

I suppose the answer depends on what you need the Bible to be. And that’s where the second axis comes into play. If you NEED the Bible to be perfectly prescriptive: detailing exactly and perfectly God’s nature, how He spoke, and how He expects us to act in every circumstance, such that your good behavior guarantees you a spot in heaven, then you probably also need a perfectly inerrant Bible, so that you have some guarantees about the accuracy and reliability of those prescriptions and the acceptability on Judgement Day of your earthly behavior.

But what if, instead, we’re willing to see the Bible as the written record of a couple thousand year long history of people encountering God in dozens of unique circumstances, different cultures, different existing frameworks of knowledge and religion and society, and incrementally having their understanding of God challenged and refined bit by bit, so that we read a picture of ever-closer, ever-more-accurate relationship between God and man? Well, then we can perhaps begin to accept that the earliest records of God’s “commands” to man may have been imperfect, and their description of God’s character and nature may have been imperfect – either because the stories were imperfectly recorded, or because perfectly-recorded stories reflect an imperfect understanding of what God really required or who He really was… or somewhere along that scale of imperfection.

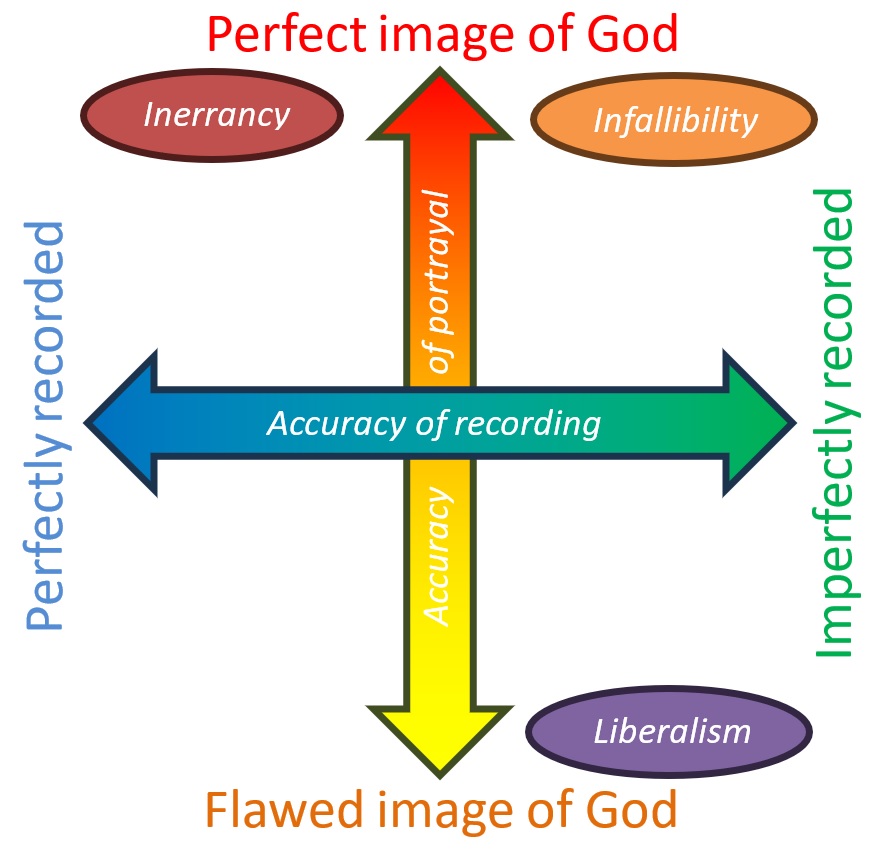

Much like the plot of an interpretive spectrum, I could also show this accuracy thinking on a plot, with the portrayal of God on one axis and the recording axis on the other. Inerrancy requires perfect recording and a perfect image of God; infallibility allows a flawed document to nonetheless perfectly portray God’s nature to mankind.

Within such a framework of imperfect understanding or recording, anywhere other than in that inerrancy corner, the obvious differences between Old Testament and New Testament become less troubling: as Jesus Himself said, “You have heard it said,” “but I say to you instead.” Even at the midpoint of the Bible, Jesus was challenging what He called “sayings” (even though directly from Torah) as being incomplete or inaccurate or superseded.

For example, taken as a whole, the Bible seems to present a view of God as infinitely loving, and even explicitly saying that “all shall be saved” (1 Tim 2:4) and strongly desiring all mankind to be redeemed. It’s really, really, really hard to reconcile this later depiction of God with an earlier depiction of a God who intentionally drowns nearly every single human and animal, burns entire cities with fire from heaven, or commands the slaughter of entire people groups. But what if those depictions of God were mistaken, based in a time-relevant but immature expectation of their God? This doesn’t (in my mind) invalidate the stories in any way: it sets us up as future readers to see the progression in God’s revelation to mankind and our ability to correctly perceive His character. It doesn’t require us, then, to do some pretty wild mental gymnastics to call those acts “loving” and square up two radically different deities for a single consistent picture of God. It allows us to see the humanity in the document, pointing towards the perfection of God. It’s incarnational: a perfect God being revealed within the limitations of something lesser.

As a result, what I’m discovering is that as I move away from the literal and historical corner, the requirement for the prescriptive interpretation also weakens. If the descriptions of God’s commands and His actions and His character or nature are based on stories that seem to cry out for updating or improved understanding as we learn more about God, then it seems far more descriptive than prescriptive.

So I find myself in roughly the opposite corner of Bible interpretation than I used to be: moving from literal/prescriptive, towards mythical/descriptive. This seems to be where many progressive Christians live, although I’m not as far into the corner as the most liberal Christians.

Crucially, I’m no less convinced of the Bible’s value to me than I was when I lived in the fundamentalist corner: I just see it as having a drastically different thrust or direction or emphasis than I use to see it. I don’t look at the Bible for step-by-step commands and perfectly reliable checklists of how to behave and think – which works great… only until life throws an unavoidable curveball at your faith. Instead, I see it as paving the way for me in dealing with a complicated world of shifting sand, showing me how to chase after God and deal with disappointments and struggles that continually challenge my simplistic view of Him and His character and His commands. A story thousands of years long shows an arc that is eminently useful in my decades of life. It explicitly gives me permission to have my understanding of God grow and change.

Now, within this revised understanding of the Bible, I encounter a new challenge to understanding: what is God up to with this imperfect document?

I can see the Bible as a centuries-long set of stories of people – very different than each other, in very different circumstances – encountering God in new and challenging ways, where each generation and each hero encounter situations that upend their view of God and force them to reconsider their underlying beliefs. Nearly every hero story in the Bible has such elements – and many of them are praised for pursuing God through the changes. From that perspective it seems to me quite reasonable that the overarching story that the Bible is trying to tell me is that my own view of God is insufficient. If I believe God actually had an active role in crafting that Bible, crafting the story that God is trying to sink into my own soul and heart, I cannot reach any other conclusion: no matter what was written down before, no matter what I previously put my faith in, it’s reasonable to believe that God is going to intrude upon my own life in some way that confronts what I know about Him, showing it to be either wrong or at the very least quite insufficient. And I ought to expect that to be an ongoing challenge, not some one-time event.

This kind of feels to me like a commentary against the doctrine of cessationism. Technically, that word refers to the idea that the Holy Spirit’s active working of miracles and tongues and prophecy were only vital and present during the time of the writing of Acts and the Epistles, and that with the passing away of the original disciples, the Holy Spirit’s visible acts also ceased. But I think that idea of cessation could be equally applied to the general principle of the Lord confronting His people with new and unforeseen aspects of His nature and His commands, such that through the entire Bible’s history there was never a settled, final, fixed, perfect doctrine to which we can point as “the answer.” Even in the later books of the New Testament, James and Peter and Paul (or those writing in Paul’s name) continued to debate aspects of how to live and hold faith. There simply isn’t any final chapter that says “Okay, you guys, here’s what it all means; all that other stuff was good debate, but let me lay it down for you.”

And if it was never fully settled during the time period described by the Bible, and if God means to continually challenge us with increasing measures of His presence and His living active word, then it seems utterly reasonable to infer that even the writers of the New Testament didn’t have the final answer. Why would God end His story – and our story as His children – so soon? It seems equally reasonable to infer that God is continuing to pour out His character into His people in increasing measures – which requires us to grow and expand, to be the “new wineskins” able to hold increasing and new and fresh measures of His Spirit.

Let’s be real here for a moment: if I were going to design a religion, and write the owner’s manual for that religion, I’d certainly be a lot less ambiguous, and I’d write a much better closing summary, making it super clear what was expected of its adherents. But we don’t have anything like that. So I can only conclude that, if God is real and capable of intruding on our affairs, He must have designed the Bible the way it is: messy and complicated and full of challenges. Why? It must be something about how God wants the scriptures to work for us – or in us.

And I think this is quite supportable by the Scriptures themselves. As Hebrews 4:12 says, “the word of God is living and active.” And as Jesus said of the Holy Spirit in John 14:26, “the Advocate, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in My name, He will teach you all things, and bring to your remembrance all that I said to you.” As Jesus also said in John 14:12-17, “he who believes in Me, the works that I do, he will do also; and greater works than these he will do because I go to the Father.” These and other such verses seem to clearly convey the idea that we haven’t seen it all, and we should expect to grow beyond even what the Bible itself teaches.

As a former member of a Christian tradition of literal/prescriptive Bible reading, I can already hear the objections arising: “if you can’t trust the Bible as perfectly accurate, with immutable descriptions of God and His commands, and self-consistent from cover to cover, then what can you trust? You might as well throw it all away, because you’ve lost your faith.”

Except that, from my new view from the other corner of this diagram, my answer will be: what I’ve learned to trust is not my own interpretation of the Bible, or even someone else’s interpretations from generations ago. Instead, I’ve learned to trust God directly, in the form of the speaking and gentle urging of the Holy Spirit, drawing me into closer and closer relationship with Him, learning to trust His rhema spoken revelation in each moment, no longer placing my faith in whatever logos translation I use, but directly in the One it reveals. Because I’ve concluded that I cannot implicitly trust any human-written, human-edited, human-translated bit of paper. But I can implicitly trust the perfect One who it imperfectly reveals. Because, in the end, one thing it reveals across all 66 Biblical books (or 73 or however many in your Catholic or Protestant faith tradition) is a God who loves and desires relationship with His children, and that He pursues us diligently and oh so patiently, and I trust that He’ll speak to me increasingly clearly and keep me centered on Him, even if the written Bible isn’t as perfect as I’d really prefer it to be.

What, you might then ask, keeps me from being deceived (as I’m sure some of you readers or listeners are already convinced that I am)? If I can’t trust the Bible to keep me centered, I can make it anything I want!

Sure, that’s true. If I were not explicitly determined to be constantly repenting of wrong beliefs, and inviting Him to redirect me every day if necessary, I’d worry too. But I’ve made a longtime practice of giving God my “yes” as often as I can. He knows – and I keep reminding Him (and myself) too – that I WANT to be closer to Him, that I WANT Him to refine me, that I don’t want to walk in error (even if error or apathy is more comfortable, which it often is). And if that means surrendering my immature ideas of what the Bible is, or should be, even if that means surrendering my certainty and absolute faith in and need for a perfect document explicitly crafted directly by the Divine hand and breath of God, then I’ll surrender even that.

Bottom line, if I can trust God to have actually inspired men to write and compile the scriptures and to have done even some of the various miracles they record, it’s not really hard to trust Him to lead me through the path He wants me to take of interpreting them His way, of understanding Him exactly as He wants for my life. And with all the grace that He showed to flawed people in the Bible, I also trust Him to deal graciously with my flawed attempts to follow Him honestly.

So for now, suffice it to say this: I’m now of the opinion – and open for God to change my mind about it – that He didn’t stop speaking when the last Bible book was committed to hardcopy, that just like He wasn’t fully revealed in the Old Testament, He still isn’t fully understood or revealed by the “completed” Bible, and that we’re allowed – and even expected – to find ways that those former writings were incomplete. Because although God doesn’t change, we do, and our understanding of Him is incomplete, and He is constantly revealing Himself to us in new and culturally-relevant ways. As C.S. Lewis wrote, “Come further up and further in!”

Wow I’m blown away, not only because you have a great way of articulating this but because this is what I feel led to know and have been having thoughts and revelations about. To think that there’s someone else out there who thinks this way is so freeing. I thought I was going mad! But yet so convicted…